A serial killer is slashing his (or her) way through the yummy mummies of Arizona. Philandering Paul (who still loves his wife, as he reminds us every four-to-five minutes) becomes a suspect when police link his new tyres to one of the murder scenes. When yet another housewife is offed, Paul struggles to provide an alibi without divulging the details of his latest extra-marital affair. Fortunately his wife has learned of the affair, and doesn't hesitate to reveal all to the police. Is Paul now vindicated, exonerated and in the clear? Not quite...

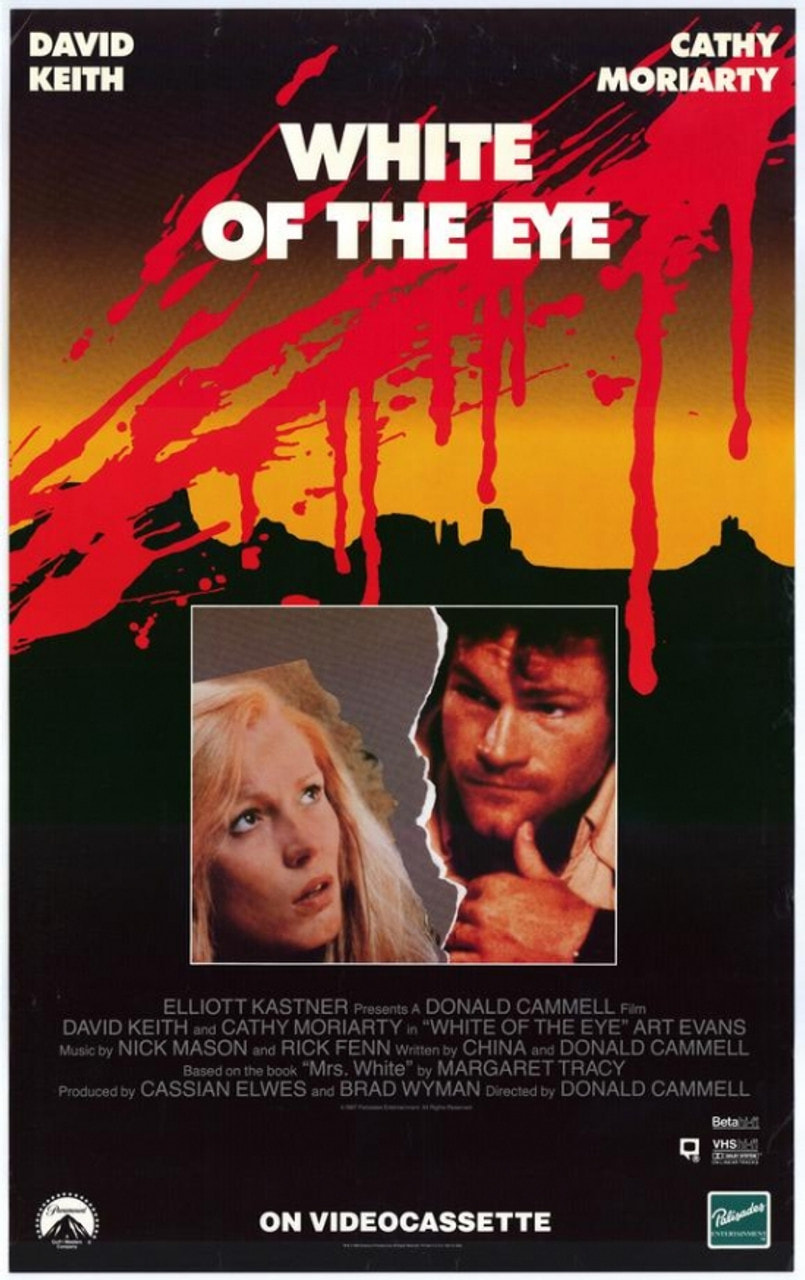

{SPOILERS THROUGHOUT!] This is a bit of a mental film, which befits its creator, Donald Cammell, who was, to cast aside propriety for a moment, a bit of a mental man. It both reveals the killer extremely early, and, bravely (/mentally) has the main suspect turn out to be actually guilty. Yes, that's right - Paul is the middle-aged mummy murderer, and a dog murderer, and almost a daughter murderer (to be fair, she is really, really weird, and her mother tries to muscle in on the daughtercide when she drops the kid from a second storey window from which she herself refuses to jump).

The final forty minutes of the film are pretty out-there; about as far out-there as Paul, with his ranting about black holes being analogous to the darkness at the heart of women (if you want to talk about darkness at the heart of something, take a look in the mirror mate). It's not just Paul's behaviour that's off-kilter - his wife Joan settles in to spend a night in his company after discovering a load of dismembered body parts under their bathroom sink. The lengthy scene in which she settles in to hear him rant and rave has a curiously banal air of domesticity which is pretty unique, although the scene's novelty does become somewhat wearing the longer it goes. The remainder of the film plays out as a kind of cat-and-mouse game, albeit one in which Paul doesn't really seem to have much interest in actually catching his mouse; his interests lie more in the field of making odd noises and rubbing blood/paint on his face.

While the ending isn't very gialloey (although Formula for a Murder, to give one example, isn't exactly dissimilar in structure), the first half of the film contains many nods to the filone. We get black-gloved killings, multiple extreme close-ups of eyeballs and some pretty out-there camerawork (including an early snorricam effect) and editing. Saying that, the editing style owes everything to Cammell's own ideas about time and pacing, and nothing to the influence of gialli.

The lengthy flashbacks seem to initially exist to provide backstory for John and Joan's relationship history, but turn out to be performing much the same function as the standard giallo flashback - ie to provide a bit of context and background for the killer's behaviour.* The police, initially quite perceptive in immediately landing upon John as a likely suspect, gradually fade away into nothing, proving ultimately as effective as most giallo cops. But enough of reductively listing the giallo connections and influences of this film.

Well, actually, the rest of my notes are about aspects of the film which aren't unrelated to gialli-which makes sense, I suppose, given the subject of this blog. So here are a few more observations: the fetishisation of the local cop's teeth, replete with extremely crisp foley work, is a truly bizarre moment, which performs absolutely no function narratively (and aren't such non-sequiturs an integral part of the Italian genre film?). The cop character seems to be being floated as a red herring, as is Joan's ex-boyfriend Mike, who plays a crucial role in the finale and is probably 7/10ths as mental as John - he witnessed John essentially conducting a blood rite with a dead deer, and decided to keep the info to himself until such a time as he could get the drop on John with a rifle. Also, perhaps it's no surprise that the police investigation fizzles away, given the chief detective's penchant for washing his hands in toilet bowls (although, to be fair, his knowledge of ancient Indian rites is incredibly prescient, albeit never used as anything but quasi-exposition for the audience).

The stalk-and-slash murders are fairly gialloey (and slashery, albeit the attempts at suspense and the preponderance of eyeballs probably tips the balance towards the former). The intrusion of a bright white sneaker into one scene jars somewhat, and screams 80s (which is fine, though, cos it was made then). The music is fairly perfunctory, although the opening theme seems to be trying to leap into the main music from Inferno, teasing as it does the main riff from that song. But overall, the music, murders and mystery aspects don't quite hit the mark in purely giallo terms.

But that's not really the point, as this isn't really a giallo. It's a crazy film about a crazy guy, specifically about that crazy guy's dual existence as crazed killer and... somewhat loving father and husband (albeit one who does cheat a lot).** There are a lot of unique touches befitting the idiosyncratic mind of its creator (/adaptor, as it was a very loose adaptation of a book), with the best, for my money, being the scene where Paul's interrogated by the police, who get Joan involved for a bit of good cop-bad cop (or good cop-bad wife), making for some pretty off-the-wall viewing. And consider her fury when she thinks her husband is innocent of murder and guilty of adultery, and contrast that to how she acts when she discovers that he's actually an insane serial killer... Crazy stuff altogether. And it's these myriad idiosyncrasies of tone and logic which seal this film's status as an honorary giallo, as out there as anything the likes of Andrea Bianchi or Mario Landi could dream up.

*The bleached-out grainy images of these sequences recall the technique used by Jess Franco to delineate flashbacks is his masterpiece Nightmares Come at Night, although given the extremely limited distribution that film had until the 2000s I can conclusively assert that the similarity is entirely coincidental.

**Duality being clearly something in which Cammell, writer and co-director of Performance, held a keen interest.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed