Jane, recovering after losing her unborn child in a car accident, is haunted by nightmares which fuse memories of the crash with images of her mother, whose murder she witnessed when she was five. She begins to see a figure from her nightmares, a stern-looking man with steely-blue contact lenses, following her around London, and begins psychiatric treatment at the behest of her sister. Jane also makes (very fast) friends with a new neighbour, who encourages her to abandon the psychiatric mumbo-jumbo and instead pursue a sensible course of black masses. Increasingly unable to discern between hallucinations and reality, Jane sinks ever deeper into the darkest recesses of her colourful mind.

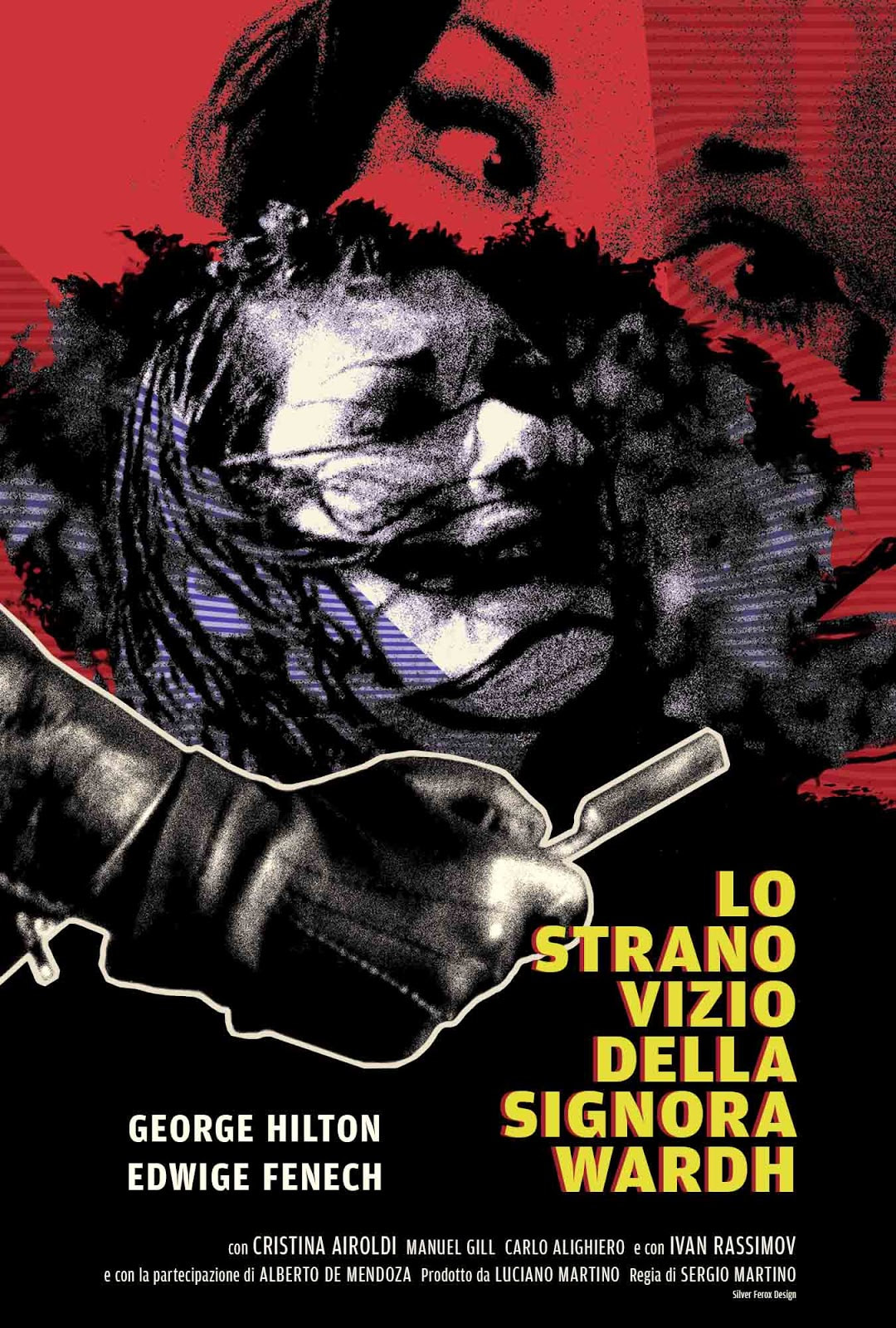

As you may have gathered from that synopsis, this film is very much a case of style over substance. This is very unusual for an Ernesto Gastaldi-penned piece, although Sauro Scavolini, who was also given screewriting credit on several Gastaldi-Martino collaborations, and Santiago Moncada, credited with having originated the story, may have had more of a hand in shaping the story. I suspect that Martino himself can also claim much of the credit/blame for the finished product.

That product resembles, in its first half at least, a directorial exercise in generating suspense.We're treated to almost the full gamut of typical giallo set pieces-stairwells, subways, isolated parks, home invasions and the classic car-that-won't-start are all thrown in there. All that's missing is an underground car park chase. None of the set pieces result in a murder, however, which represents a big change of direction from Martino (storywise; his filmic direction is as stylish and impressive as ever).

The troubling pregnancy (the termination of which occurs before the film's start), the apartment block setting and the intrusion of a devil-worshipping cult into a young woman's urbane lifestyle are elements which were obviously borrowed from Rosemary's Baby, as is the face-off between psychiatry and witchcraft. Whereas in Rosemary's Baby the coven's magic-and the devil himself-turns out to be real, here the coven is apparently a front for an extremely elaborate attempt at an old fashioned inheritance-grab.

It doesn't pay to peer too closely at the mechanics at work here, or else you'll find yourself wondering if the huge cost exacted by the coven, both in financial and human terms, was really worth it to inherit a few hundred grand, and whether there wasn't a more efficient way to clear the way for said inheritance than trying to literally scare Jane to death. You may also wonder why the hell Jane was encouraged to attend sessions with Dr Burton. You may wonder why on earth, having apparently established(ish) the grounded-in-reality motives and methods of the coven, we suddenly discover in the last reel that Jane has a form of second sight, thus thrusting the film once more into the realm of the fantastic.

The answer to that last thing you've wondered is, most likely, because Sergio Martino, or his writers, wanted to explore the possibilities for generating tension by staging the same scene twice. Again, we see that the plot here is the flimsiest of flimsy, with the film really being nothing more (or less) than an exercise in style. But what style-it's possibly Martino's best-directed film, with every scene masterfully staged and captured. He's one of the best exponents of maximising the visual impact of his locations, which, given the pace at which these films were shot, he'd likely have only seen a very short time before filming. He's always able to find an unusual nook in which to place the camera, or plan an audacious pan to showcase the location in its full glory.

Edwige Fenech as Jane, supported by George Hilton doing his best John Cassavetes impression, turns in probably her best acting performance here. And she needs to; she's little more than a pawn, to be moved around on a whim in order to facilitate the staging of the next set piece. Her bonding scene with new neighbour Mary (not that kind of bonding, alas) is the most egregious example of this; there's a black mass scene to be had, so we rush through the first flush of friendship in barely ten seconds' worth of screen time, which is all it takes for Jane to arrange to see Mary 'sometime soon', then narrow that down to the next day for lunch, which becomes a morning's shopping followed by a lunch date. They're suddenly best friends, planning their lives around each other, and Jane is ready to agree to anything her bosom buddy suggests, including participating in a weird mass orgy in a big country house.

The cinematography, editing and music are also top notch, right from the get-go. One shot in the opening nightmare, a crane shot which lowers to ground level with the cameraman then walking out towards the action, was replicated almost exactly in Goodfellas almost twenty years later (it'd be pushing it to suggest that Scorsese or Michael Balhaus had seen this film though, but it shows that great minds sometimes do think like other great minds).

|

|

It's far from perfect, and although you won't have a clue what's going on (even after it's over), if you can accept the film's shortcomings, and focus on its pleasures, there is much fun to be had here.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed