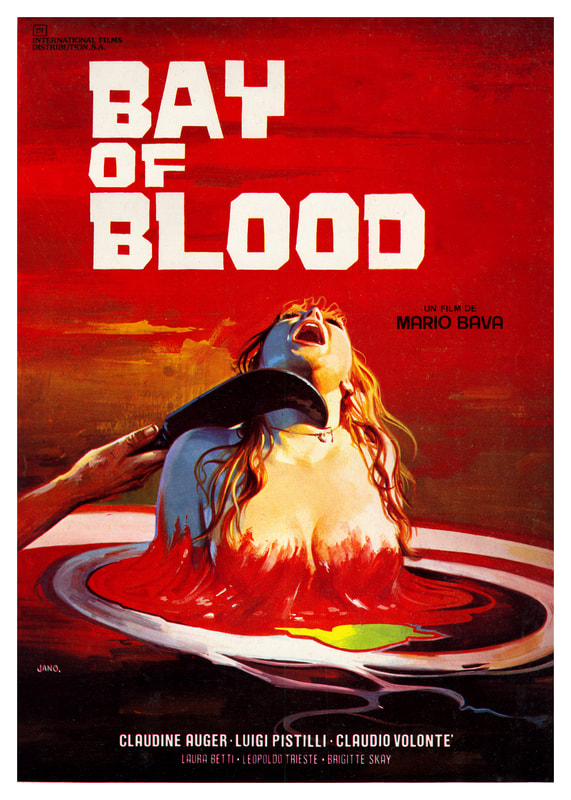

A year after the death of his wife Helen, which he believes happened after he threw her from a balcony while blackout drunk, Oliver Bromfield returns to his country mansion with his new wife, Ruth, in tow. Oliver's widowed stepmother, who is in love with him, and his loner stepsister, who was in love with Helen, offer a welcome that could be generously described as 'cool' to the lovebirds. Cracks show in the marriage almost immediately, as Oliver suffers from nightmares about his wife's death, and Ruth suspects that the official line, that Helen fell after suffering a dizzy spell, may not be true. After a loooong build up, we get a few murders towards the end, followed by the least-surprising reveal of all time. And that's your lot.

The aforementioned reveal really does take the breath away. (Prepare for spoilers.) In some ways it did surprise me, because having the most obvious suspect turn out to be the killer (seriously, if you've made a casual guess as to their identity based on the above synopsis, you're correct) is definitely an unusual approach to a mystery film. There isn't even an ulterior or alternate motive offered, which would retroactively imbue what we've seen with some sort of depth and hitherto obscured meaning; it's all so mind-numbingly straightforward. The first dialogue scene in the film, which is between Oliver and his horny stepmom, takes place directly after his wife's funeral and contains all the material you'll need to construct the key which unlocks this mystery. (This scene was excised from the Spanish version, which would at least heighten the chances of the running time hitting double digits before the viewer knows all.)

I did briefly consider whether this was a clever double-bluff, a la Eyeball's approach of offering up every single character as a suspect at one point or another, but I genuinely don't think that was the case. One neat touch which I did like was the roll-call of still images of the remaining suspects after each murder (we begin with 5, and end up with 3). The killer is slap bang in the middle of this list every time. A couple of characters-Oliver's new wife Ruth, and the doctor who certified Helen's death an accident-aren't included in the list of suspects, which would have made their being the guilty party/parties a neat twist, with the stylistic flourish of the stills playing an active role in the film's presentation, and obfuscation, of the mystery. But no such luck. The killer is right there, hiding in plain sight. Or rather, acting extremely suspiciously in plain sight, and being proffered as one of the main suspects by the filmmakers.

Of course, there's a chance that we were meant to pick up on Ruth and the doctor's exclusion from the list of suspects, which would back up the theory of the solution being an attempt to bamboozle the audience into overlooking the most obvious suspect. I myself suspect, however, that I'm giving them altogether too much credit with this line of theorising.

To briefly expound on more of the film's flaws, Ruth's suspicions regarding her husband develop literally overnight, after he mumbles incoherently in his sleep while having a nightmare. (It is refreshing to have the tormented soul struggling with the boundaries of reality being a male character; most housebound horrors favour females for such roles.) She immediately decides that he's lying about his ex's death, and takes off to see the local doctor. He, showing shockingly little disregard for confidentiality, or his licence, admits to having falsified the death report, which claimed that Helen had suffered from regular dizzy spells in the run up to her death. This lazy scene, apart from a few brief conversations Ruth has with the gardener and housekeeper, account for the sum total of the investigative angle of the film. It also precludes Ruth and the doc from having being in league together (although it doesn't absolve them separately; we know the doctor's been complicit in covering up a murder-even if he thinks he's just protecting Oliver-and Ruth's 'investigation' could be designed to throw fresh suspicion on her husband, whose estate she's conveniently in prime position to inherit).

There's occasional nudity, which is often provided by garishly-lit body doubles, and some classic lesbianism-as-imagined-by-a-man. There's some of the worst poor man's process (where actors are filmed in a stationary car which is rocked slightly to simulate movement) you've ever seen. The murders aren't anything special, nor is the soundtrack. In fact, as stated above, nothing is special. You spend most of the running time searching for hidden meaning or hidden depths, only for the end reveal to confirm that yes, the film is actually that straightforward. Maybe that's the biggest twist of all, or a satire on how we continually search for deeper meaning in life, only to ignore its nuts and bolts.

Maybe it's not though; maybe it's just a pretty shit giallo.

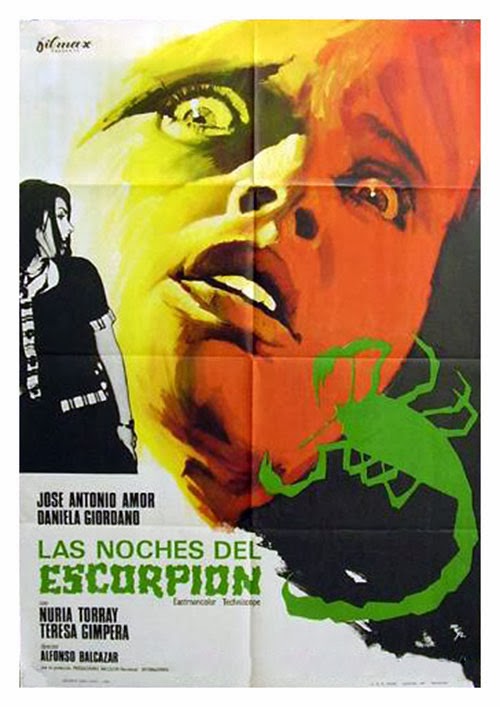

PS Jose Larraz, who was responsible for some of the most atmospheric housebound horror films of the 70s, had a hand in the script. Given his films' preference for style and atmosphere over plot, it might have made sense for him to direct this, given the lack of all three in the end product. Or maybe someone who can construct plots could have written it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed