She then gets rather better news when it turns out that Kurt had taken out a $1m life insurance policy a year before he died, with Lisa the sole beneficiary. The policy was taken out in Greece, where Kurt spent much of his time. Lisa is followed from the insurance company's office by another former lover, a drug addict who blackmails her because of a letter she once wrote expressing the wish that her husband died. When she calls to the addict later that evening to retrieve the letter, she finds him dead and the letter gone.

Lisa flies to Greece, pursued by Peter Lynch, an investigator working for the insurance company. She is summoned to a meeting in an empty theatre by Lara, her husband's Greek lover, who attempts to get Lisa to hand over half the fortune. The incriminating letter was stolen by Lara's 'lawyer', Sharif, who attempts to attack Lisa. She flees before he can get to her, aided by Peter, who followed her to the theatre.

The next day, Lisa takes delivery of the policy, in cash. On returning to her hotel room she's brutally stabbed to death by a leather-clad assassin. Her corpse is discovered that evening, with the money gone.

Peter is taken in by the police as a suspect, but, in part thanks to John Stanley, an Interpol agent, declaring that he's probably innocent, he's released. He follows Stanley to Lara's apartment, where he narrowly escapes being killed by an axe-wielding Sharif.

Peter takes time off from following people and gets close to Cléo Dupont, a French photojournalist who's covering the case. After they return to his hotel room to find it trashed and searched, they switch rooms and make love. Lara and Sharif, who were behind the trashing, agree that they were mistaken in their suspicion of Peter, and decide to continue their quest for the money the next day. However, on returning home, Lara is stabbed to death by the same assassin, who also dispatches Sharif, who returned to try and save her.

Cléo gets a telephoned tip off about the murders from Stanley. The local police inspector, Stavros, has his men watching Peter, so they knew to call the hotel to get a hold of her.

Peter and Cléo continue their romance. After leaving her apartment and realising that he's left his car keys there, Peter returns and just about foils an attack on her by the assassin. Stavros and Stanley don't seem to believe his story, and seem reluctant to speak to Cléo to corroborate it.

Lisa's lover, who she was with when the plane exploded, is also in Greece, and is killed by the assassin.

A small cufflink found at the scene of Cléo's attack sparks something in Peter's memory, and he enlarges an old photo of Kurt Baumer to reveal that the cufflink belonged to him. He suggests that Baumer didn't take the ill-fated flight, and has instead been offing the various people that stood between him and his $1m. The police apparently buy this theory, and send Peter and Cléo off on a romantic cruise. They'll pretend to be hunting Peter as the chief suspect, but really they'll be tracking Kurt.

Cléo notices Peter swimming towards a small island with a large, full bag, which is empty on his return. At the same time Stanley discovers that the cufflink from the crime scene was a Turkish knock-off of an original.

Cléo steals off the boat while Peter's sleeping, and discovers the money stashed in a secret cove which is only accessible through an underwater passage. Peter confesses that it was he who killed Lisa and Lara, and Lisa's lover, a steward, was his accomplice and had planted the bomb and staged the attack on Cléo. She stabs him with a harpoon gun and makes a break for it. He pursues her to the nearby rocky island, and is about to dispatch her when he's shot dead by the police, who've found them by tracking the location of the boat's last broadcast.

Stanley had found the original complete set of cufflinks at Baumer's mansion, and we all know that no right thinking man has two sets of identical cufflinks, so this cleared him. Plus, the dead steward's girlfriend had been wearing a similar cufflink, which she said her boyfriend had brought back from Turkey, when the police interviewed her. Deciding that Peter was the only person who could have left the cufflink in Cléo's apartment as a deliberate ploy to frame Baumer, the police knew they had their man (somewhere out at sea).

Cléo leaves hospital, and Stanley swoops to steal her from under Stavros' nose, telling her that he was waiting for "a beautiful day, and a beautiful girl" before leaving Athens.

Making the eventual killer the police's number one suspect is a fairly ballsy move, and Peter's use of his steward accomplice to alibi himself for the attack on Cléo isa classic piece of misdirection The only problem is that, beyond Tom Felleghy as an insurance company worker, and a peeping Tom neighbour of Cléo's, both of whom have one scene in the film, there are precious few other suspects, especially once the steward is dispatched. Stanley, the incompetant Interpol agent, is the obvious other suspect, although his increasing immersion in, and enthusiasm for, the investigation makes this unlikely. And Stavros seems too removed from the Baumers to have had a hand in their demises. Baumer himself, who is at one point a suspect despite being dead, does have enough of a presence throughout the film to be viably considered for the murderer, but gialli very rarely introduce a killer as a previously-unseen character. Of course, the characters within the film don't have recourse to this line of logic.

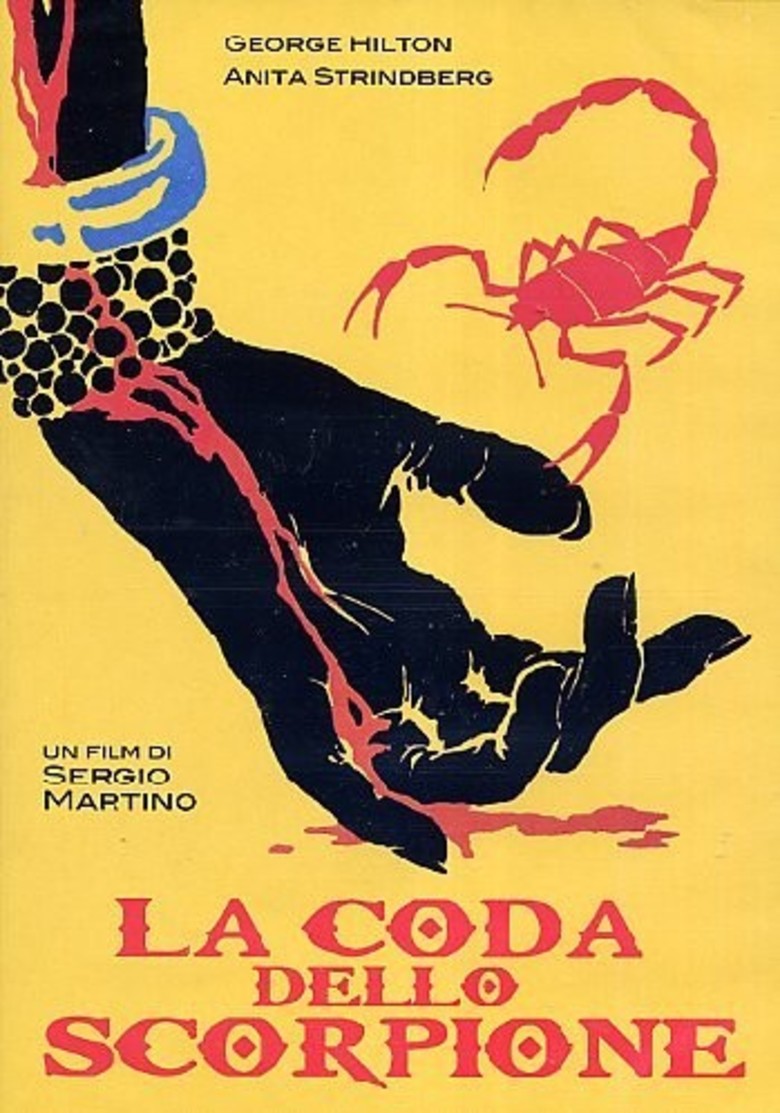

It's a great, fun film though, bearing the fingerprints of both Martino and Ernesto Gastaldi, the main scriptwriter, throughout. Not for Gastaldi the then in vogue Freudian psychosexual killers of Argento; he was resolutely an inheritance plot artiste. He prided himself in his airtight plotting, something lacking from the vast majority of gialli, and on first viewing he seems to have done a great job here. As with almost all constructors of tightly-wound plots, though, he's had to cut a few small corners here and there.

(I'd like to preface this examination by saying that if I went through the plot of almost any other giallo with as fine a tooth comb as this, I'd still be writing twenty years from now. In a way-I hope, anyway-drawing attention to the occasional slight deficiencies of the plot will enable to you simultaneously see its strengths, and to appreciate the twisting and turning complexity of the average Gastaldi script. His films tended not to have the traditional amateur detectives, simply because there wasn't room to accommodate them on top of all the plotting and killing.)

It's extremely difficult to come up with a mystery plot which simultaneously contains airtight logic and enough misdirection to surprise and delight the audience. Only the very great (Agatha Christie probably being the greatest of all) could pull this off even occasionally. Gastaldi probably qualifies as one of the great plot constructionists, but on this occasion, he does resort to, shall we say, 'convenient anomalies' to aid in the subterfuge.

To explain what I mean by this, consider that most, inferior, whodunnits contain basic plots, with the mystery element enhanced by having several characters act in a manner that is designed to draw the audience's suspicion upon themselves. They usually do something, say something or stare after someone in a manner that strikes us as strange, out-of-character. This is the low-end of the 'convenient' behaviour spectrum.

Gastaldi, in Scorpion's Tail, uses a higher form of convenience. Characters do and say things that seem normal enough (or suspicious enough, where needed), in a manner designed to misdirect the audience. These misdirections are, for the most part, subtle enough that they don't immediately spring to mind as anomalous once the killer's identity is revealed.

(An example of a low-end anomaly would be the moment in Scream where Billy, standing alone, berates himself as being "Stupid!" after upsetting Sidney and sending her crying to the toilet, for a planned ambush. This moment exists purely to try and trick the audience into thinking that Billy [who has been foregrounded as a suspect in a similar manner to Peter in Scorpion's Tail] is innocent; he wouldn't have behaved like that if the camera wasn't on him.)

The anomalies in Scorpion's Tail are chiefly filtered through the police's behaviour and observations. First, though, there's the small, large matter of the $1m, around which the plot revolves. Lisa insists upon receiving the money in cash, presumably at the urging of her steward lover, with whom she plans to go to Tokyo (and he, in turn, is presumably acting at the urging of Peter). Without easy access to the money, Peter's whole plan falls down. We never find out why exactly Lisa has agreed to cash the bond, though. This point is quickly lost and forgotten, though, amid the fast-moving forward momentum of the film.

Now, to the fuzz. When we're first introduced to John Stanley, he states that he feels Peter is innocent, based on no evidence whatsoever. Still, the more an audience, who are already conditioned to see Peter as not guilty, since the film is barely half an hour old at the time, hear that he's innocent, the more they'll believe it. He also, later, states that he believes the killer is a sex maniac, killing random women This despite only two women (and one man) having been murdered at that point, with both of them having strong connections to Kurt Baumer (this isn't one of the convenient anomalies; it's just damn poor police work).

Later, when Cléo thanks Stanley for calling her in Peter's hotel room (in the Italian language version anyway; in the English one he phones her paper and tell them to call the hotel) with the tip off to Lara's murder, Peter seems indignant that the police knew where she was. He's told that, as he's still a suspect, he's under police surveillance. Are we to assume, then, that the surveillance team knew which room Peter and Cléo moved to after his original one was trashed, but they didn't notice him leaving to commit a double murder, and subsequently returning?

Moving on to the steward, his exact relationship to Lisa varies slightly in the different language versions. In the Italian one, he and Peter are fully in cahoots, and are planning to lure Lisa to Tokyo, where they'll do away with her and steal the money. In the English version he's fallen in love with Lisa, and is planning to go to Tokyo with her to escape from Peter (this doesn't sit well with his apparent immediate resumption of his Greek relationship, nor-crucially-with the cashing of the bond). In both versions, he's outside Greece for the first series of murders (in Turkey, getting the cufflinks, for at least part of this time), and is thus alibied. The police reveal, in the Italian, Gastaldi-penned version, that they were already aware that he was a lover of Lisa's, so surely they'd have hauled him in after the plane explosion? If they're nominally watching suspects, such as Peter, surely the steward also warranted a tail once he'd returned? The steward's murder was always going to incontrovertibly link him to the case, so Peter's attempt to portray him as a stooge of Baumer's does make a lot of sense. However, the logic he suggests as being behind 'Baumer's killing of the steward (partner-in-crime who knew too much) is the exact logic which led to him committing the actual murder. If the police buy the steward as an accomplice, why can't he be Peter's?

Later, the police do claim that Peter was always their main suspect, and they were just waiting for him to slip-up. If this is to believed, his eventual slip-up, detailed below, isn't anywhere near as amateurish as the police's letting him sail away, unobserved, with an innocent woman in tow.

And, why did Peter swim out to deposit his money in the secret cave in the middle of the day? Why not wait til nighttime and lightly drug Cléo? If he managed to stash the money without her finding out, the police would have had no case against him, bar Stanley's cufflink hunch, which wouldn't have stood up in court. Peter's managed to evade Cléo before (not to mention the police surveillance), when he popped out of his hotel to kill Lara and Sharif, so why does he suddenly display such incompetence?

It's easier in books, where you tell, rather than show, to construct a perfect mystery plot. Hearsay and the recounting of events hold equal weight to 'present' incidents in books, as they're all just words on a page. Once visuals, which portray rather than describe events, are introduced to the mix, it's harder to show enough to keep the audience interested, but hold enough back to retain the air of mystery. Of course, directors such as Dario Argento were able to get around this by adding a subjective element to the visuals, which weren't always to be trusted (Hitchcock, too, had done this back in the 40s, with Stagefright).

Gastaldi and Martino had one of the greatest writer-director partnerships of all time because Gastaldi's fastidious attention to details and logic was perfectly complemented by Martino's excess of style, which made everything they made so watchable. It's tempting to hope for one, final pairing of the two, given they're both still alive. But perhaps it's better to appreciate what we they've already given us, and enjoy their one mystery that can't be fully solved, despite my best efforts here-why are their films so bloody good?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed