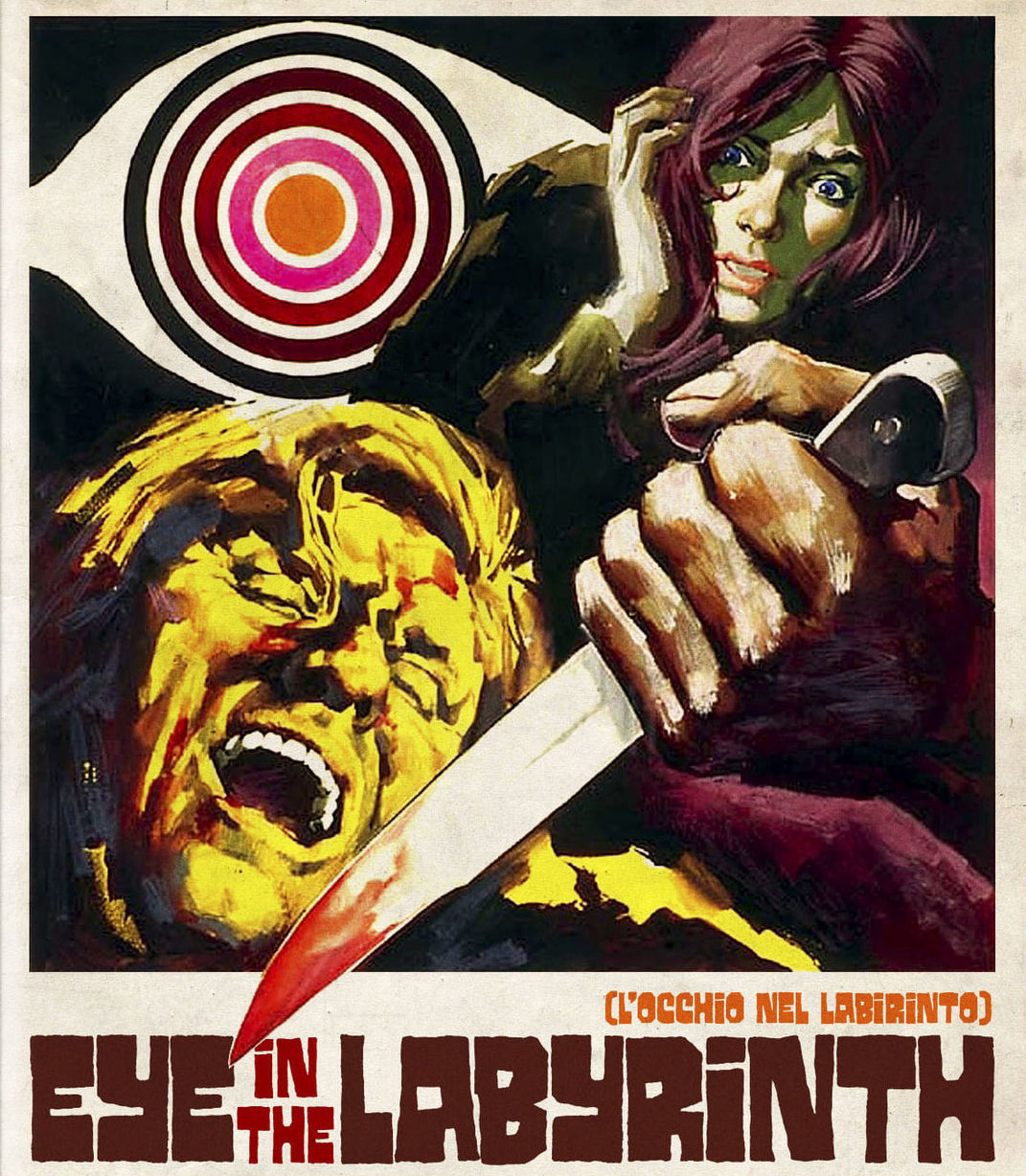

A young woman, Julie, wakes up after dreaming of the brutal slaying of her psychiatrist boyfriend, Luca. Discovering that Luca is nowhere to be found, she follows an oblique clue shouted by one of his patients and ends up in Maracudi, a remote village. There, she survives an assassination attempt and befriends a local gangster, Frank. After explaining that she's trying to track down her boyfriend, Frank advises her to visit a local villa where arty types hang out (psychiatrists being the artiest of arty types). Julie duly pays the villa a visit, and finds a bizarre collection of twentysomethings lounging around sunbathing, all seemingly under the thumb of Alida Valli's matriarchal Gerda. Despite mounting evidence that Luca had indeed visited the villa, all its inhabitants initially deny having seen him, so Julie decides to stick around to sunbathe topless, seduce Valli's toyboy, and occasionally ask questions about her missing boyfriend.

I don't blame her for not fully concentrating on the hunt for Luca-he's an absolute scumbag. He's a sociopathic, drug-dealing rapist, who even violates his doctor/patient boundaries by dating Julie, one of his patients. The monster! Julie takes the constant revelations as to Luca's true character reasonably well-as in, she doesn't really react at all to them-although the transference of her affections to sexy Louis, Alida Valli's toyboy, suggests that they may have had some effect. Or else she's just trying to blend in with the rest of the villa residents by being a shit.

This is one of those films in which pretty much everyone is a horrible, horrible person. It almost doesn't matter who the nominal 'killer' is (and there are actually 3 different killers, in a way); everyone is guilty to some degree. Adolfo Celi's Frank is one of the more likeable characters, his main sins apparently amounting to his being a gangster who was run out of America, and being unable to resist the occasional urge to hop on Julie. To be fair, he does take 'no' for an answer on the third or fourth occasion of its utterance.

The plot, as stated, doesn't really sustain itself for the length of the film. Once we get to the villa it's fairly certain that Julie has arrived at the end of her investigative journey, and all that's left is to narrow down the list of suspects. She proves less than adept at this, and over the course of the film you can almost feel her slipping from the driving seat of the investigation, to be replaced by Frank (which restores the standard male-at-the-helm giallo scenario). The film's reveal is one of those ones which might piss you off a bit (and it's one which Umberto Lenzi used a few years later and later claimed, in an out-of-character display of bombast, was a startlingly original type of ending), but it does just about stand up to scrutiny.

One of the main reasons why the film is more-than-bearable throughout the final hour is the location. Rivalling The Sister of Ursula for the best giallo scenery, the villa and its environs are simply stunning. What's more, Caiano sure knew how to film them to maximise the impact. The film straddles the divides between several different type of gialli-the standard 'foreigner abroad investigating a possible murder' (a la Bird with the Crystal Plumage) segues into 'an isolated group by the sea' (a la 5 Dolls) which then morphs into an 'unstable young woman adrift in an evil world out to get her' film (a la Autopsy). These subtle changes of direction help to maintain interest, as we know 90% of what happened to Luca, but struggle to get a firm handle on the final piece of the puzzle. There's also a novel twist on the hoary old trope of 'character knows who the killer is; character doesn't immediately divulge identity of said killer; character dies before getting a chance to name killer'. Here's a tip: if you ever find yourself in a giallo, don't feel the need to impart such news face-to-face, shout it from the rooftops! Or just go to the bloody police.

A couple of other things to note are Sybil Danning's presence, playing a semi-virginal type (who still gets her baps out), and the reasonably progressive presentation of a transgender character, who is accepted for what she is by everybody (apart from that asshole Luca. Honestly, I'm glad he's dead). It also features some charming naif artwork which recalls that in Bird with the Crystal Plumage, down to the fact that the painting depicts a brutal murder. Its painter, a local simpleton, paints what he sees, in stark contrast to the arty types in the villa, who distort the world around them, taking photos of isolated body parts, recording natural sounds and re-editing them into music, and even changing their own gender. The film, which ultimately is also about distorting reality, won't blow your socks off, but no film ever made has had the ability to move socks.

|

|

PS If you watch the Code Red Blu of the film, be prepared for some extremely poorly integrated new foley work. These sound effects are far crisper and louder than the rest of the soundtrack, and the final scene. in particular, suffers greatly for their inclusion.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed