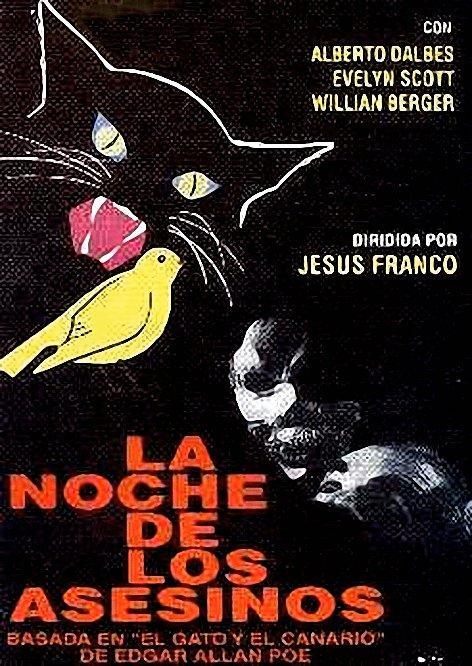

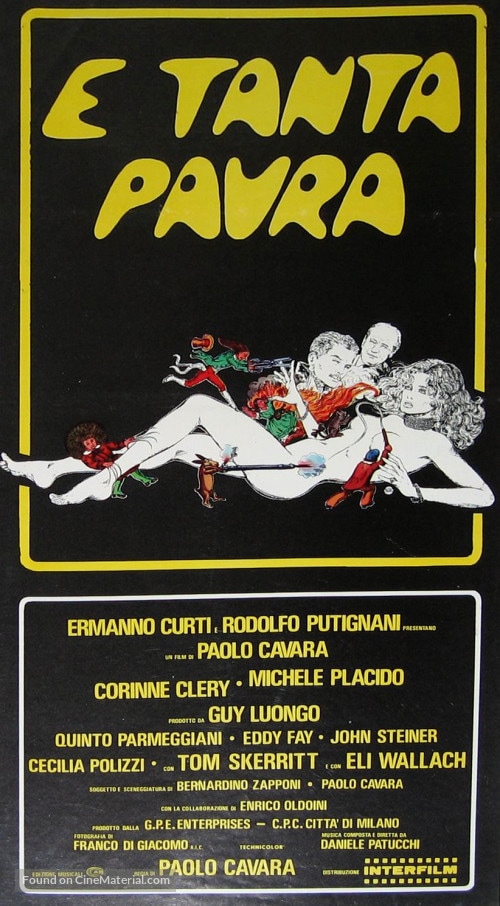

The plot is fairly standard, surprisingly so for Franco. A masked killer stalks the halls of Castle Marian, killing family members and servants alike, basing the murders on the four elements (earth, air, fire and water). As people gather for the reading of the Lord Marian's will, doubt is cast as to the true identity of the murdered patriarch, and a second, entirely different, will further confuses the issue. A Scotland Yard detective teams up with the local Louisiana policeman to try and crack the case before everyone winds up dead.

As it happens, most of the cast do wind up dead (with one of them literally murdered by wind), which slightly undermines the mystery aspect of the film. The killer can really only be one of two or three people (at most), which means that it's not the hardest guess you'll ever make. However, the precise motive of the killer isn't necessarily obvious, and, as it turns out, neither is their true identity, so there's still plenty of room for a swing and a miss. This secondary aspect to the mystery, with the past events at the heart of the motive strongly hinted at in dark exchanges between any number of shifty characters (without giving too much away, let's just say that very, very few characters in the film are actually innocent), leads to Franco attempting to get away with hiding the killer very much in plain sight.

Even setting aside these past events, there are actually multiple killers at play within the film. One is masked, and thus assumes the role of central killer by default, but two other characters also account for three deaths between them. One of these, played by William Berger, is so shifty and suspicious throughout the film (his wife initially refers to him as being "capable of murder", then outright references his murderous past) that it's almost confusing. We know he's a killer, but surely he can't be the killer? (No, he can't.) Berger isn't the only shifty-eyed character, though, and this is one of those films where the 'real' killer isn't necessarily the last person you'd suspect. Indeed, on repeated viewings, the killer acts incredibly suspiciously, even getting some choice soundtrack stings to highlight their reaction to a piece of news.

The end revelations seem tolerable on first viewing, but there are certain gaps in logic which become apparent when one thinks back over proceedings. Specifically, the characters of Marian's illegitimate daughter and the notary exist in a kind of limbo, either playing an unacknowledged role in the aforementioned 'past events', or else failing to recognise the return of a key character for no discernible reason. The film begins excellently, with a terrifically atmospheric opening with Lord Marian being stalked, slashed and buried alive, and the 'two wills' twist is a good one. It doesn't quite sustain the pace right to the end (in common with its director, who often lost interest during the filming process), but it's still good fun. It's certainly far from a bottom-of-the-barrel giallo, and when you consider just how full Franco's 1973 barrel was, it's an admirable achievement.

(One final note: the credits suggest that it's based on a Poe story called 'The Cat and the Canary, which doesn't exist. It's more in the vein of an Edgar Wallace thriller, and, indeed, a German krimi.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed