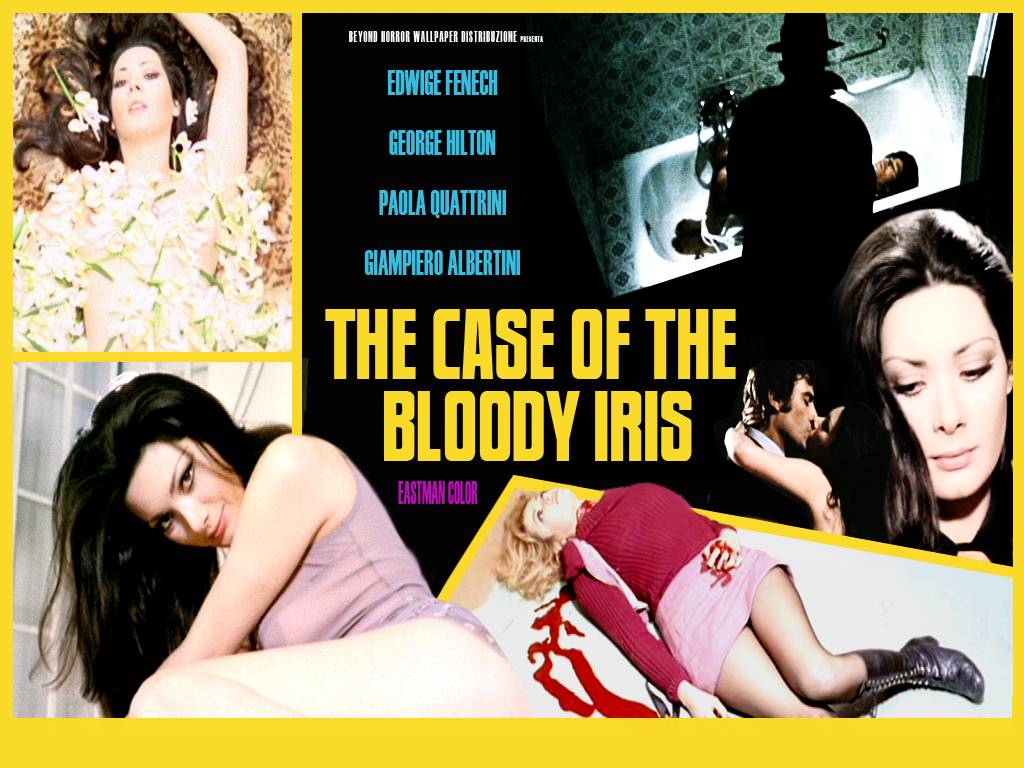

The plot, or what passes for one, involves a series of murders in and around an apartment block in Rome. Most of the victims are fashion models. An architect, who designed the apartment block in question, falls for a model. He is suspected of being the killer. Several tenants of the building have secrets. The architect decides to go on the run after yet more circumstantial evidence accumulates around him. The real killer is then unmasked.

As you've probably guessed, I'm not going to pull any punches when it comes to this one. It's strange; the set up-models and an apartment block-is ideal, the talent in front of and behind the camera is beyond question, but the film just leaves me cold.

The chief culprit is the script, which is shocking (more so than anything in the film) when you consider that it was penned by Ernesto Gastaldi (sensibly hiding behind a pseudonym, 'Ernesto Gastaldy'). The plot is paper thin, with only the police showing any inclination towards attempting to solve the murders (and limited inclination at that, as I'll show). George Hilton's architect, Andrea Barto, is bafflingly passive throughout.

He's the prime suspect from the word go, given that he knows the ins and outs of the building he designed, and was the last person to see the second victim alive (apart from the killer, and the witnesses who confirmed to the police that he'd left her on the night in question to get a taxi home). Then a stabbed girl literally falls into his arms in the street as she dies, making it seem as if he was the one who killed her. He flees the scene of the crime wearing a beige jacket soaked through with blood, which he stubbornly refuses to shed as he races through crowds of Roman onlookers. He then disappears (but makes no attempt to investigate who the actual killer is), as the police are out to arrest him, even though it turns out that the policeman who was chasing him later confirms that he had noticed that the girl had been stabbed before she collapsed into Barto's arms. And this despite his being consumed with making a sandwich in his car at the time, and clearly not noticing what was happening until the girl had died. It's that kind of film.

Barto's not the prime suspect for us audience members, though-that honour falls to Edwige Fenech-playing the model for whom Hilton falls-'s ex-husband, who initiated her into a group sex cult, and who spends his time stalking her and indulging in heavy-handed symbolism involving the titular flowers. He's obviously not guilty, though-this is a giallo, and he's too obvious a suspect. When you remove him (as the killer does, fairly early on) and Barto (who we know from the street stabbing scene is not the killer) from the equation, we're left with precious few suspects.

It's not just these two characters who act both suspiciously and stupidly, though; every single character could be described using those adjectives. Everyone, that is, apart from Edwige Fenech's menaced heroine, for whom passive is the only descriptive necessary, and her housemate, Marilyn, who is vacuous, stupid, annoying and empathy-free. That's not me being overly sexist and aggressive towards her; it's merely an accurate summation of how the film presents her character. It's a blessed relief when the bitch gets what's coming to her (that is me being sexist and aggressive towards her, channelling my inner Case of the Bloody Iris).

With female characters who are either victims-in-waiting, shameful lesbians or crazy old women, is it any wonder that the male characters don't exactly respect the finer sex? Consider the following choice lines of dialogue:

"Aw sure-we're all human, and every man wants a black girl"

Commissioner Enci bonding with Barto

"I must say you'd tempt any human being"

Predatory lesbian Sheila (who, though she isn't a man, buys wholeheartedly into the general air of sexism) sympathising with Fenech after she's attacked by the killer

"Don't trust your neighbours."

"Which neighbours?"

"The women."

Enci again, who gives no reason as to why the male neighbours are to be trusted

"It's a shame to see a beautiful girl like you wasting her talents. Try the opposite sex; that's what we're here for"

That man Enci, charming the local lesbian

It's a given that the films of the 60s and 70s display some 'alternative' (/regressive) views on female liberation, and women in general. There are other films which display far more hatred of the female of the species, yet which curiously don't alienate me as much as this one. It's possibly because at least misogyny calls for passion on the part of the hater, whereas here we just have lazy, casual disdain. The women here aren't even worth working oneself up into a frenzy of hatred.

The second victim, Mizar, is shown to be a supreme wrestler, defeating man after man in the shadowy nightclub where she works, but this is less a display of female strength than a questionable fetishising of her exotic qualities (she's black, and every man wants a black girl). I'm not sure whether the above dialogue was translated from Gastaldi's script or added by the English dubbers. Even if it's the latter, the film still leaves a lot to be desired in terms of female representation. The casting of Fenech, always a pretty-but-passive presence, is telling (although she was also shagging Luciano Martino, the producer, which might have had something to do with it).

The police, when they're not making sexist wisecracks, are also particularly stupid in this film. Barto has a blood phobia, which Fenech cites as proof of his innocence of the street murder (the detective's alleged sighting of the girl falling into Barto's arms having already been stabbed would probably trump that in the evidence stakes though). Enci replied that "it's perfectly natural for a person with a phobia like that (blood, remember) to be attracted to the sight of blood, in a way." Riiiiight.

A frenzied phone call from Fenech to the sandwich-loving detective to say that she's (erroneously) identified the killer as a burn victim who's the son of her next door neighbour is met by the following reaction: "I get the picture, you found the monster. Some of my best friends are monsters." To Enci's credit, he isn't so quick to dismiss the call, although when he searches for the alleged killer, he fails to open the doors to the massive closet in the apartment, where the burned son secretly resides.

|

As I said, there's no real investigative thrust in the film, with the characters instead channelling their energies into behaving suspiciously, in perfect examples of what I catchily termed 'convenient anomalies' in my review of Scorpion's Tail. Assuming that Gastaldi's script wasn't rewritten too much by Giuliano Carnimeo (who does direct with style, with a lot of excellent handheld shots), one can only surmise that this project was churned out quickly by the writer, probably alongside the equally-average Human Cobras, while he channelled his creative energies into his Sergio Martino collaborations. Or else Martino deserves credit as the sole auteur of those films (which I don't think is the case). Anyway, I'm rambling. Popular opinion would suggest that Bloody Iris is a top-tier giallo. Popular opinion also led to the election of Adolf Hitler and Donald Trump.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed