Will the film answer all these questions? Not really. Lucio Fulci, one of the originators of the scenario, hammered the film in a later interview, claiming that director Riccardo Freda made it at a stage in his career when he'd essentially given up trying. And, to be honest, he's not massively wrong; the most persuasive evidence being the film Fulci himself made from the same plot outline-Perversion Story-which was released one month after Double Face, and which spun similar ingredients into a far, far superior tale.

The slapdashery is evident right from the start, with some extremely unconvincing car model work in evidence on two separate occasions, as well as some dire blue screen effects for a skiing scene that was presumably some early work of the FX technician who did the surfing sequence in Die Another Day. Having said that, the film does also contain some classy moments from the off, with director Freda seeming especially at home in the stately country houses in which a large portion of the film is set. Having shown his aptitude for gothic filmmaking at the beginning of the decade, he could, and possibly did, design the camera's gliding movements around the hallowed halls while working on autopilot. We also get a very slick shot of a white car reflected in sunglasses in close up, a shot which could almost have been the inspiration for the entire plot of The Iguana With the Tongue of Fire.

Freda seems much less comfortable when it comes to directing the Happening sequence set in an abandoned warehouse, with random zooms and ragged handheld shots apparently deemed sufficient to tick all the directorial boxes. He's far from the only director of his generation (and he was among the very oldest of those) to struggle to fully get to grips with youth culture, but at least Fulci, Martino et al made an effort to come up with a visual style which was somewhat appropriate for depictions of the burgeoning scene (albeit typically a style which leaned heavily on use of the wide angled lens). Here, Freda seems to be almost refusing to direct, suggesting a strong animus towards the hippy movement, to the point that they weren't worth engaging with on any level. (There is a teeny tiny chance that Freda is attempting to depict John Alexander's own confusion by rendering his thought processes via the camerawork and editing, but I think that's a very generous reading.)

The thing is, hippies and their covert sex films form an important plot point, with Klaus Kinski apparently Happening upon freshly-shot footage featuring his dead wife. I say 'important plot point', it's actually debatable whether this film has a plot at all-in some ways it's more a series of sequential events, devoid of the cause-and-effect logic by which a plot is driven. As I suggested above, the film raises a hell of a lot of questions without necessarily being able to answer them. Things happen, people act in certain ways, and the effect is no different to the standard giallo plot (at least, the standard plot for this time-it's essentially one of Lenzi's inheritance-in-the-sunshine jaunts set in London, with John's sunshine jaunt taking place off-screen). It's just that when the cards are finally laid on the table and we find out what's going on, the filmmakers have essentially been bluffing.

The hippies make a sex film (and two distinct edits of the film, with one being subbed in for the other at a certain point of the film in a manner that would have been extremely difficult to pull off [pun intended]), and Christine, the star of the film who lures John the the Happening, is clearly involved in the grand scheme at the centre of the 'plot', but how, and why? And just what is the 'grand plan' which has been concocted by the villains (which ultimately involves more than half the cast in its execution)? It places one of the plotters in extreme peril, with a significant chance of them being murdered by their mark, for no reason-they've already committed a murder, so just make sure that the mark gets framed for that one!

There are inconsistencies and unresolved plot strands all over the place-when exactly did Christine move into her apartment? What's the significance of the ticket to Japan? We even get the resolution of a plot point that was never introduced-something about the time of Helen's death, which has either been teed up by a deleted scene, or is a victim of an on-the-fly rewriting with a resultant inattention to detail. Freda also shows a curious inability to pay off those sequences which see characters approaching, say, a chair from behind, unsure of whether or not it contains someone, or following the sound of someone's voice. Part of the problem lies in the editing-the climactic scene in which John confronts 'Helen' in a cathedral suffers from turgid editing which obfuscates his point of view for too long, but the shot selection and framing is often sloppy too.

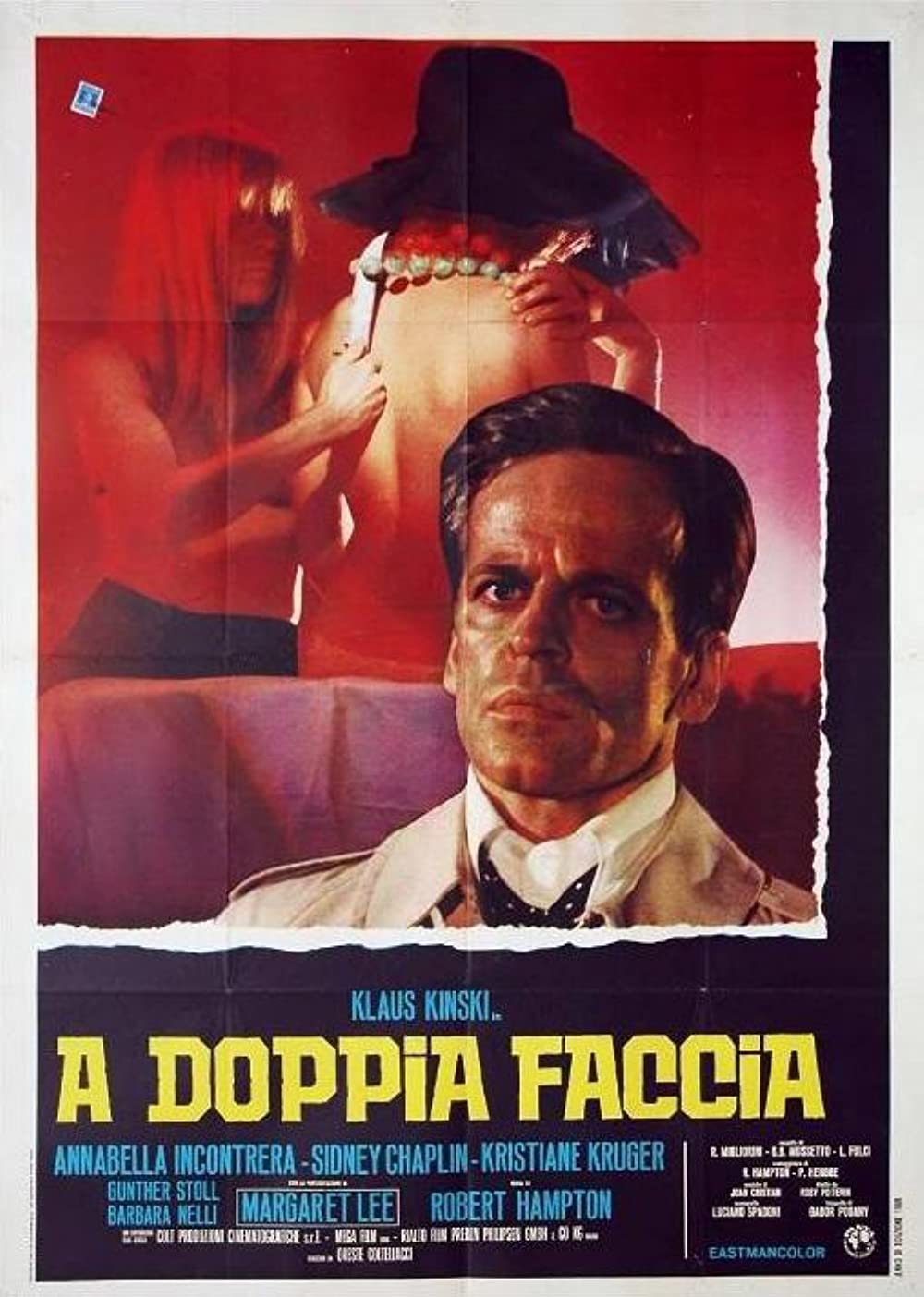

John is played by the one and only Klaus Kinski, in one of his very few non-Herzog leading roles (his first real such role, in fact). He was apparently reluctant to take the role, turning it down according to Roberto Curti because he didn't want to play a psychopath (a curious stance to adopt, because the only properly psychopathic thing about the character as he exists on screen is the person playing him). He's no-one's idea of a dashing romantic lead, but he reins in his excesses, and avoids unnecessary gnashing of gnashers, to which he was often susceptible. He does take this too far on occasion, though-witness the scene where he's showing his (step-)father-in-law the stag film, only to discover that someone has switched his reels for a different edit. Instead of speaking up and trying to explain what's happened, he merely stands there dumbstruck, something which might be believable initially, but surely you'd find your voice at some stage. He then throws the film in the fire, even though it may prove to be a crucial clue* (fortunately, much like the movie as a whole, this particular film fails to catch fire). Kinski seems more interested in transforming into a pseudo-private eye, stalking the streets of London (occasionally) wearing a trilby and trenchcoat as he seeks... what exactly? We're not sure that he wasn't the architect behind the car crash; after all, he knew his wife was cheating on him, and he stood to gain financially from her death. So, is he trying to prove that she's dead, to settle his nerves? Is he hoping against hope that she's still alive? You could argue that in order to allow for both these possibilities, the film can't tip its hat towards one or the other of these motivations; however, Klaus could insist that he wants to prove she's still alive, say, while secretly hoping that she's dead. This is a giallo** after all! As it is, he never really says anything, and the character is horrendously underwritten. Jean Sorel, the perennial whipping boy of the giallo critics, is far more compelling in Perversion Story, aided in no small part by the script and plot making it clear that his character has much to gain, and, simultaneously, much to lose.

The film's title, which on the face of it would seem to refer to the possibility of Helen's resurrection (and then her apparently disfigured visage), could also refer to something which threw me on first viewing (something which, as I've acknowledged before, may be more of a failing on my part than the film's): the resemblance between Lisa, Helen's lesbian lover, and Alice, John's secretary who is also his occasional lover. It's probably a deliberate choice-they're each the lover of one of the married couple, and one loves John whereas the other despises him, but it does muddy the waters somewhat unless you're really on your toes in terms of facial recognition (or hair recognition-Alice has longer hair). And John in many ways is also two-faced to Alice, largely treating her with disdain before he deigns to permit her to make love with him late on in the film. And, of course, there is one further instance of 'double-facing'-the devious plot which forms the centre of whatever plot the film has.

I've been pretty down on this film, but it's not actually as bad as I've made it out to be-after all, Klaus Kinski + Riccardo Freda can't = terrible. Neither are firing on all cylinders though, but Nora Orlandi, with both her orchestral score and the pop song that forms one of those kind-of plot points, saves the day by being at the absolute top of her game. There's also some great driving footage in London, and if nothing else, the film perfectly captures the passing of the torch from the old school gothic style to the freewheeling free love era. One final thought, which applies to Perversion Story as much as this film-if I had to discern whether or not a mysterious woman was my partner, I think I'd be able to state with certainty based on their manner, voice etc. And, as happens in both films, if I was afforded the privilege of seeing her boobies, I'd be left with no doubt whatsoever. Maybe that's just me, maybe I'm a pervert. But even if I am, my point still stands (ithankyou).

*It may well have been, given that the police admit that they've used illegal tactics to ensnare the mastermind behind the plot, except the second-in-command then helpfully, under no pressure whatsoever, confesses everything.

**There's been a lot written about how the film is also a krimi; nonsense-if it hadn't been financed by noted Krimi producers no-one would have even given this angle a second thought.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed