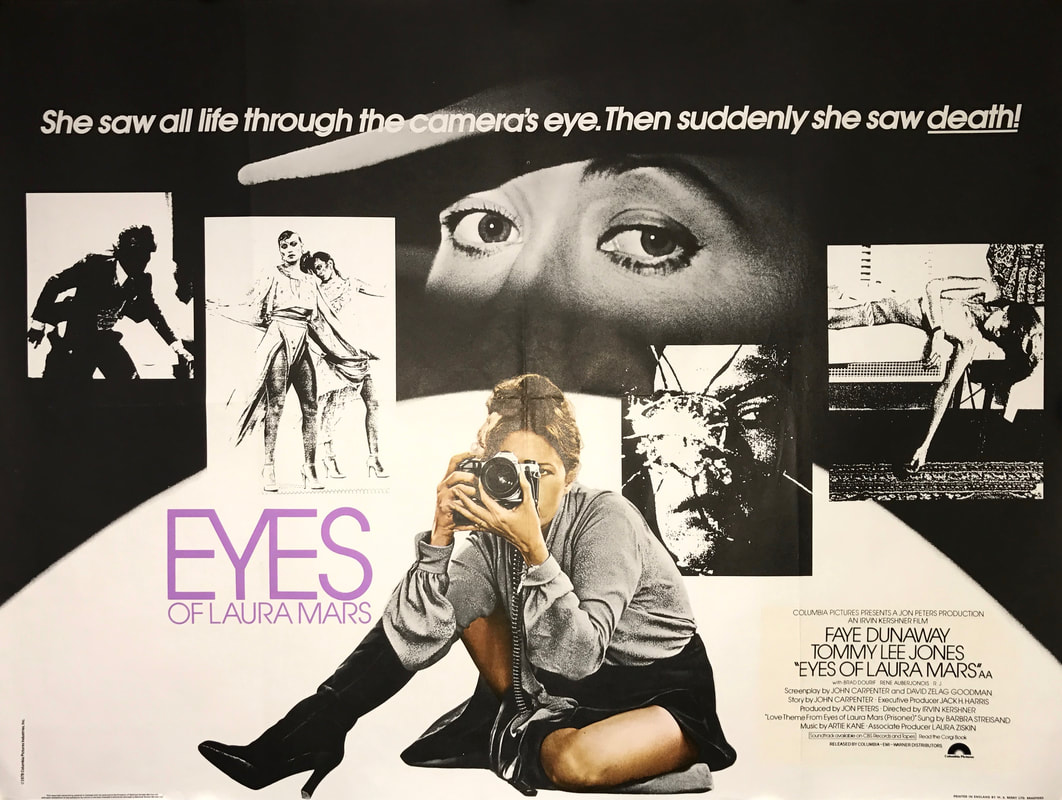

Famous, and controversial, fashion photographer Laura Mars specialises in fetishistic images of death. Specifically, dead women. Just as she's launching a big new exhibit and book, women-and men dressed as women-from her inner circle start dropping like flies. What's more, Laura, through some kind of second sight, sees glimpses of the killer's point of view as he stalks and slashes his way through her friends and colleagues. As the police 'investigate' (/ineffectually sit outside people's apartments), the killer turns their sights, and Laura's occasional sights, to Laura herself...

This film deals with a couple of fairly weighty issues: the fetishisation of violence in art, and the victimisation of women in both art and real life. At least, it pays lip service to these issues, but does it really get to grips with either? Before we get to that, I'll say that this isn't a bad film, but it's quite vanilla in giallo terms. There's very little gore, no real investigation, and minimal moments of baroque Argento-esque style. It's worth a look, though, and features some bigger names than you'd normally find in a giallo, if that's your thing (one of whom, Brad Dourif, pops up again fifteen years later in Trauma).

The story lends itself naturally to Layers. Layers of text and subtext; layers of meaning and depth. You have voyeurism and scopophilia, fetishisation and commercialisation of violence against women, and mirrors. Lots and lots of mirrors. This (mirrors) is an example of 'depth' in a film which is fairly redundant to me-seeing characters reflected in a maze of mirrors is an impressive technical achievement, and we can take it as a given that it's the film 'subtly' telling us that one or more characters have a fractured personality. And here, sure enough, the killer seems to be a bit schizo. It's a bit of a cul-de-sac in terms of opening up the film for discussion, though, much like having goodies dress in white and baddies in black in westerns. Sure, we can point out to our less cerebral friends that the director has colour-coded the characters to externalise their inner goodie- or baddie-ness, but there's not a whole lot more to say beyond this.

There's more to chew over elsewhere, though. I'm unsure of just how much Carpenter remains in the final product (allegedly not a whole lot), but the idea of Laura seeing the stalk and slash through the killer's POV did come from him, unsurprisingly given how he utilised first-person shots to such an extent throughout Halloween. Laura doubles as the film's audience during her vision scenes, observing events over which she has no control. This point is explicitly made when she tells Tommy Lee Jones' inspector "I can't see what's in front of me. What I see if that," and points at an image on a screen. And yet, by creating such images in her working life, she also doubles as the filmmakers; commercialising artistic violence. She attempts to explain away her career choice by saying that she seeks to depict "moral, spiritual, emotional murder." She says she can't stop murder, but can "make people look at it."

Does she really want to do this to remind people of how horrible the world is, though? Or is she merely seeking to justify her life choices by hiding behind a smokescreen of spurious and specious reasoning? Why exactly is making people look at murder preferable to the alternative (ie, not making them look art it)? Similarly, John Carpenter, and Irvin Kershner (to a far lesser degree), made money by making horror films. They can claim that they're making people look at murder with altruistic intentions, but are they really trying to convince us, or themselves? For the record, I don't think it's necessary to justify commercialising violence; murder existed before films were invented, after all. Even if a work of art inspires a copycat murder, the killer is obviously mental to begin with and would no doubt have figured out a way to commit heinous acts without artistic inspiration.* This is, nonetheless, something that any person who sends violent images out into the world must grapple with at some stage. Or, at least, should grapple with.

Making Laura a woman is an interesting move. A cynic might argue that it's simply efficient filmmaking, allowing one character to simultaneously open up the dialogue about representations of violence on screen and fill the woman-in-peril role. Similarly, is her second sight indicative of women being more in tune with the world around them, or is it merely a way to film murder scenes in a disorienting manner while also keeping things relatively studio-friendly and bloodless? (Neither; it's almost certainly to allow for an exploration of the point of view, as suggested above.)

To return to Laura's dual function as both purveyor and potential victim of violence, why shouldn't she be allowed to be both? People who complain about woman being reduced to the role of disposable victim in films have a (generally) valid complaint, but the fact remains that, in real life, women statistically are far more likely than men to be victims of violent crime. Female actors generally seem more physically vulnerable on screen than men, so it's easier to create a sense of danger and dread. The fact that Laura fulfils this role while also earning her corn by taking advantage of female vulnerability adds a delicious layer of irony to proceedings. You could argue that she's not a good female role model, but fuck it-why should she be? Non-white males in films tend to be viewed as being representatives of their gender/race/sexuality, which has always sat uneasily with me. In many ways viewing characters in this way has the opposite to the desired effect; the intention is to push for greater representation of and appreciation for 'marginal' groups, yet when confronted with an example of someone from such a group, their individuality is immediately tossed aside, and their personality is viewed as being representative of a whole. This is unfair on both the group and the characters themselves.

That Laura adds a veneer of sex and sexuality to her images is also interesting. Is photographing sexy women, and photographing imaginary acts of violence against sexy women, in any way offensive? Well yes, in that plenty of people in the film express outrage at Laura's work, which would undoubtedly have met the same response in the real world. And just look at the response to slasher films, and to Dario Argento's comments about preferring to kill beautiful actresses in his films. But, then again, the most inane utterance can cause offence (or faux-offence) in the Twitter age. I don't want to get all PC-gone-mad about things, so I'll say that the characters in the film, and IRL, have every right to protest Laura's work. But, at the same time, I don't think she's unequivocally crossed any line. As a woman, she's within her rights to interrogate and present female sexuality as she wishes (again, as long as she doesn't cross any lines). If you don't like it, don't consume her work! Feel free to protest it too. But just don't go calling it offensive; it's offensive and distasteful to you, not objectively offensive, and there's a difference.

The fashion backdrop also works as a reference (intentional or otherwise) to Blood and Black Lace, and the combination of fashion and second sight anticipates Nothing Underneath. The issue of the second sight is an interesting one; initially we're faced with the possibility that what Laura's actually experiencing are flashbacks to murders she herself has committed. This reduces the film to a very basic either/or scenario, so it's made clear reasonably quickly that the visions are real. This, of course, places the film at the edge of the supernatural subgenre, although the second sight is the only such element in the film. Its existence is never really addressed, and it basically functions as either a plot gimmick or subtext gimmick (or both), depending on your outlook.

Aside from the sexuality of the fashion shoots, there's also a slightly cloying post-coital scene, which is very much a Hollywoodised version of a typical giallo sex scene. The emotions expressed within it are fairly over-the-top and sugary, but the Italian gialli weren't immune to such flourishes either. As stated at the outset, there's very little visual style here, despite the possibilities opened up by the fashion shoot-setting and second sight murder scenes. One reasonably atmospheric sequence sees Laura running through a vast empty studio, and the moment when she realises the killer's identity features some classic Eurocult style-a push in on the killer's face followed by a zoom into the Eyes on Mars.

Regarding the identity of the killer, there's no real investigation to speak of, with the police instead seeming to adopt an approach of waiting to happen upon the killer to presenting themselves 'in the act'. They spend much of the film functioning as ineffectual bodyguards, with two murdered characters meeting their demise while apparently having police protection. SPOILERS This may not necessarily be indicative of poor policing, though, depending on who exactly was providing said protection. END SPOILERS

The Big Reveal, replete with dolly and zoom, is one of those that comes about three minutes after anyone with half a brain would've figured out the identity of the killer for themselves. The film further tips its hat by having one of those classic 'disembodied voice' moments, when one character tells another that everything's OK now and the threat is vanquished. As I've previously noted, when the person doing the reassuring is heard but not seen, you can be reasonably sure that things are very much not OK, and the owner of the voice is, in fact, the threat. Here, there's no reason why they couldn't have shown the voice owner as he speaks the reassuring lines. I'm guessing that it wasn't such a clichéd trope in the 1970s as it is today. In fact, a huge amount of horror movie clichés go back to this time and this year, and this writer (the writer of this film; not me). This isn't the best 1978 John Carpenter-related film; it might not even be the second-best-I haven't seen his TV movie Someone's Watching Me (note the continued theme of eyes and seeing). But it's definitely in the top three.

|

|

*I would rather that violence wasn't fetishised, and was instead shown in more true-to-life ways in films. I think any 80s gung-ho action movie is more morally dubious than something like Last House on the Left, which follows its depictions of violence in an honest manner through and past the acts themselves.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed