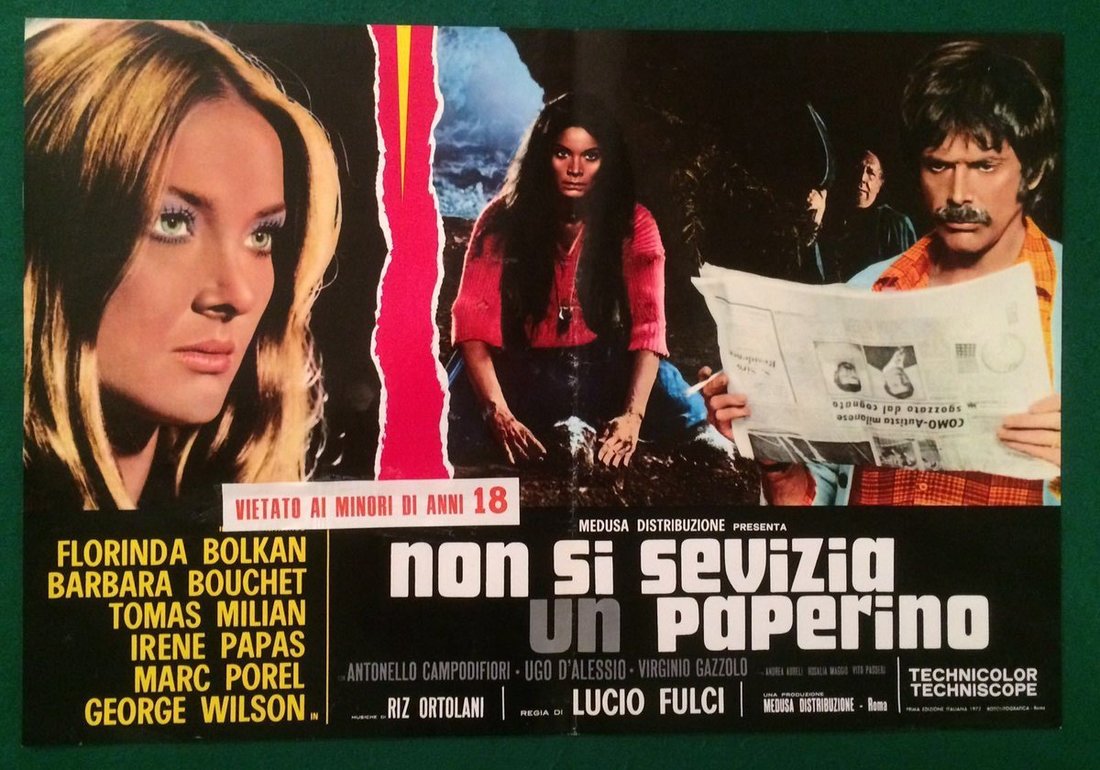

In Accendura, a small town in Southern Italy which is connected to the rest of the county by a modern motorway, someone is murdering young boys. The local simpleton is initially suspected, after he's found to be behind an attempted blackmailing of one victim's parents. However, it turns out that he merely came across the child's corpse and, sensing a money-making opportunity, buried it before making the call. The town's attention then turns to local witch, La Maciara, who has been missing for over two weeks. The police manage to track her down and she confesses to the crimes. However, it turns out she was merely using voodoo against the three children, and didn't physically kill them. After her release, she's brutally set upon and murdered by the fathers of the deceased. Reporter Andrea Martelli and recovering drug addict Patrizia, meanwhile, form an alliance to try and get to the bottom of the murders, even as the film does its best to push Patrizia as a suspect. Patrizia then sees the decapitated head of a Donald Duck doll which she bought for a deaf and dumb girl placed among the tributes for the killer's latest victim. Using some fine extrapolation skills, she and Andrea concoct an explanation for the girl's proclivity for dismembering dolls which also points the finger at a suspect for the murders. They're not quite right, but enough in the ballpark that the real killer is outed, just in time to fall to their death in a shower of sparks and crushed papier maché.

If you haven't seen this film, you should probably stop reading here, as most of what I'll be discussing will be spoilerific. Starting now. The main concerns of the film on a thematic level are the superstition and insularity of small-town Italy, and the power, and abuse thereof, of Italian institutions, especially the church. This is, as far as I can make out, the second giallo in which the killer is revealed to have been a priest, after Who Saw Her Die?, which opened after principal photography had begun on this film. It seemed to open the floodgates, with many, many more religious killers appearing in future films, suggesting that Fulci (and Aldo Lado) was articulating what a lot of artistic types were thinking.

It's difficult to discern who bears more of Fulci's scorn, the townsfolk or the authority figures. It's difficult to even know if he sympathises with Patrizia, one of the nominal leads, given that she's trying to extricate herself from a world of drugs and partying, and enters the film lounging naked and (mostly) jokingly trying to seduce a child. She's certainly shown in general as possessing, for the most part, good intentions, but, then again, she's also highly foregrounded as a suspect. This could be Fulci's way of admonishing her for her licentiousness. Likewise, Andrea isn't exactly the most driven investigator; he's motivated as least as much by the thoughts of getting a scoop as by any need for justice to prevail.

And is it even justice? (Yes, it is, but I'm asking a rhetorical question here.) The children who are murdered aren't exactly cherubic innocents. They smoke, they spy on people having sex, they slag off the local simpleton for doing exactly the same thing, and they generally seem like Normal Kids. It's actually refreshing to see such a portrayal of children, which is far removed from their troubling representation in Dallamano gialli, for example. And, unless I'm very much mistaken, I believe that Fulci intended to present the children in such a realistic manner, the better to act as a mirror to highlight the flaws and vices of the grown-up characters.

What I mean by this is that the way the adult characters view, and treat, the (normal) children tells us everything about their own personae. Patrizia sees the kids as burgeoning sexual beings, and is clearly something of a sex-fiend herself. The local priest, who steadfastly ignores Patrizia's flirting, sees the kids as loci of purity and innocence, at risk of corruption from the wider, wilder world. He proudly boasts to Andrea of banning certain publications from the local newsagents, as part of a fight to protect the town from said wider world. La Maciara believed that her deceased child was the spawn of the devil, and seems to hold a similar opinion of most adolescents, showing her general superstition.

The witchcraft practised by La Maciara and her 'mentor' Francesco is apparently closely related to religion (even though the local priest doesn't seem to have any real relationship with them). This seems reflective of Fulci's wider view of religion, which he saw as hypocritical and nothing but dressed up superstition. And, even though the murdered boys haven't been sexually abused, the film does seem to be quite prescient about the misuse of power in the church which would be exposed over the following decades. La Maciara is one such (tangential) victim of this power, having been brought to the saint-obsessed Francesco for an exorcism as a youngster. She became pregnant as a result of his rituals, eventually losing her child (whom she considered to be the spawn of Satan). Everything in her world goes back to children-she's murdered because of her supposed role in the local murders of children (the fact that the townspeople still consider her guilty because of her witchcraft also showing their own superstition and small-mindedness), she became a witch after the exorcism incident in her childhood, which led to her own deceased child. The last thing she sees is a car full of children driving by on the new motorway, a symbol of familial unity which is forever out of her reach.

The authorities, represented by a local and regional police force who combine to tackle the murders, don't exactly come out of the film in credit either. The local policemen, while possibly being less superstitious than the average townie, are very much complicit in having allowed the insular nature of the area to flourish. They seem extremely tolerant of the mob mentality which prevails in the town, and ultimately prove clueless when attempting to solve the crime. Even the out-of-towners fare little better, being reduced to ciphers through which we get to see the strange ways of the locals.* For the first two thirds of the film the police do play a prominent role in proceedings, partly to give us an insight into the ways of the town, and partly (I reckon) because the investigative plot wasn't beefy enough to sustain more than a few minutes of Andrea and Patrizia poking around late on, so instead we're presented with the repeated failures of the po-po.

To return to Patrizia, her opening scene is worth discussing in further detail. Her behaviour towards young Bruno is certainly predatory and paedophilic in nature, but she seems to be acting more to amuse herself than possessing any designs towards actually seducing the child. It's still undeniably creepy (and a bit sexy, when it's just her on screen), and possibly does give some weight to Don Alberto's views of the wider world being corrupting; Patrizia having been born locally but reared in a big city, where she came into contact with drugs and sex and rock and/or roll. Either way, although Bruno spent his last night on earth drawing naked women on his copybook, it's not as if he wasn't a horny little kid before meeting her, so Patrizia has merely given him food/fodder for thought; she hasn't changed the course of his life irrevocably. Not like a certain religious nut does.**

The mystery is serviceable, although it clearly wasn't Fulci's main concern, with the end deductive process being hurried and stretching credulity somewhat. The fact that this is (again, to the best of my knowledge) the second giallo to feature a priest killer would certainly have given the end reveal added punch for contemporary audiences. The film's cinematography is extremely stylish, albeit with one or two clunkily-shot dialogue scenes, but for the most part it looks gorgeous. Fulci's economy as a director is in evidence in several shots which combine zooms with tracking, with constant reframing to keep the action moving. It's the cinematographic approach which allowed Jess Franco to be so prolific around this time, but here it's executed far more smoothly and stylishly. The soundtrack is magnificent, and Fulci's love of dogs, and use of their barks and growls to menacing aural effect, is very much in evidence. He also uses very ballsy editing and framing to heavily hint at the identity of the killer (check out a track through the church after Bruno's mother shouts that she knows the killer is there), presumably banking on the audience's reverence for the church to preclude them from having any suspicions towards it.

Fulci's extreme lack of such reverence, also evident in The Eroticist and Beatrice Cenci, drives this film. It's a powerful film borne of powerful feelings, and one that anyone who dismissed him as a gore-obsessed hack should be made to watch on repeat, until they can't take it any more and throw themselves off the nearest electrified cliff. Or until they admit they were wrong, whichever.

*There's also a strange interaction where the head of the investigation, upon being told that La Maciara's child was rumoured to have "lived for a couple of years... kept hidden away, because it was the son of the devil," responds by saying, seemingly without irony, "a natural assumption." I think the line reading may have been deficient here, otherwise the implication is that the sophisticated big city policemen are just as susceptible to superstitious nonsense as the locals.

|

|

**When watching the scene again, pay attention to the shots which have Bruno and Patrizia in the same frame; Bruno is clearly played by a dwarf, so anyone who's worried about the actor having been corrupted can rest easy (and don't go killing any kids either).

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed