This was a joke; a self-aware filmmaker cleverly highlighting the level of control he'd had over the film we'd just seen, while simultaneously poking fun at his own ego. The credits of Sonno Profondo resemble those of Robinson's 'The House on Dame Street', but without the self-awareness.

One of my biggest bugbears when watching independent films (and you'll have to indulge me quite a lot on this before I go on to say more interesting stuff about the film) is credit-whoring. I wore a lot of hats on my giallo The Three Sisters, and am mentioned several times at both the beginning and end of the film, but have always conflated the main roles into a single 'written, shot, directed and edited by' accolade, which is situated at the top of the end credits.

Look at any 'proper' film-the director's credit tends to be at the end of the opening roll, but is occasionally the first of the end roll (c.f. Quentin Tarantino). You don't end the opening credits and open the end credits with the exact same citation. In fact, credits never get repeated; Pulp Fiction is, as stated at the beginning, a Quentin Tarantino film, but his directing and writing nods, which, as stated, kick-off the end credits, are technically a separate billing. Likewise, if the opening credits contain a list of the principal players, post-film we see not just their name, but the role they've played (if memory serves, Pulp Fiction may not actually follow this rule).

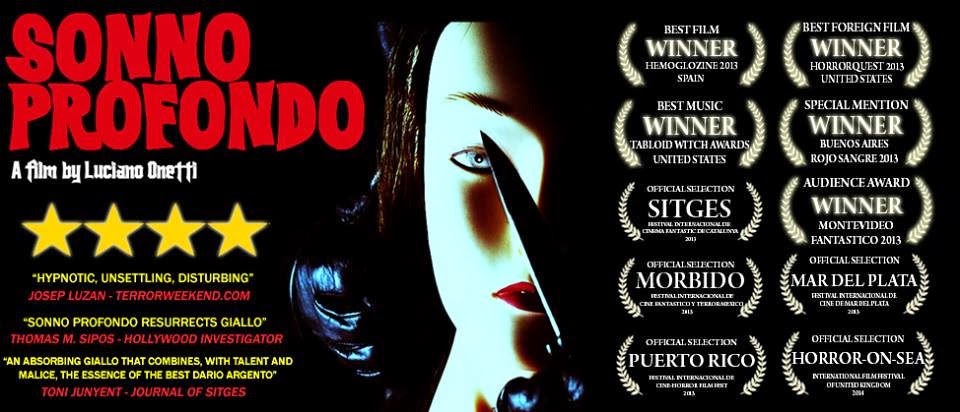

One thing that tends to distinguish amateur productions is the repetition of credits, often to pad out a short running time. Sonno Profondo is indeed an extremely short feature, running to just 66 minutes, so even the most egregious padding wouldn't take it up to 'normal' feature length. I can say this with confidence, as Luciano Onetti has indeed indulged in Robinson-esque levels of padding. I also got the impression that it wasn't actually intended as credit-padding, rather it was ego-padding, ego-stoking and ego-stroking. The brief interview contained on the US disc, which sees him speaking portentously about the film while wearing sunglasses indoors, backs up this assertion. The good news is that Onetti's film (I'm pretty sure it was directed by him anyway, I'd need to see a fourth directing credit to be certain) is pretty damn impressive.

It's definitely not for everyone. I actually had to watch it twice, on consecutive days, to get a handle on it; my concentration on first viewing being hampered by an itchy leg, tiredness, sickness and underestimating what would be required from me as a spectator. It was actually more watchable on second viewing, as I was approaching it as an active viewer, having realised, too late to salvage my initial screening, that it was more than the giallo trope-fetishisation I had initially assumed it to be.

It does indeed indulge in image-fetishisation; the entire film is graded to resemble an old 1970s print that has seen better days. 90% of the film is comprised of POV shots too, so you'll certainly get your fill of leather gloves and straight razors. The POV camerawork may prove a turn off to many viewers, but I actually liked it a lot. Bear in mind, though, that one of the Youtube comments left for my first feature film suggested that the cameraman must have been drunk and high, so I may be slightly partial to wonky handheld images. On first viewing I did find myself pining after a while for a Herschell Gordon Lewis-style flat 2 shot of characters talking against a wall (there's also very little dialogue in the film), but, again, once I knew what I was getting myself in for, the second time it was all good. The decor, and props, are all extremely retro and stylish, and Onetti has certainly stretched the presumably-miniscule budget (unless he was lavishly paying himself for all the roles he performed in the production) impressively far. The fake blood, too, was brilliantly 70s; thick, gloopy and bright red.

The style (or lack-thereof, as some would have it) does somewhat obscure the plot of the film, but, all the same, there is a definite plot here. It's one that isn't spoon-fed to the viewer, for although the film does end with a couple of fairly-standard revelations, they won't mean as much if the viewer hasn't been carefully cataloguing the imagery, and occasional aural clues, of the ten or so distinct sequences which comprise the rest of the film. Onetti, in his sunglassesed interview, specifically states that the film was designed to be more accessible on a second viewing, and this did prove true for me.

Not everyone will respond to the fractured manner in which plot information is relayed, particularly when it comes on top of such a heightened visual style. In my recent piece on Blood and Black Lace, I commented that old-fashioned mysteries often offered up clues to the attentive viewer, whereas gialli offered nothing but red herrings. Sonno Profondo, which has the barest minimum of characters, can't really offer anything in the way of red herrings, but the presentation of the pieces which form the whole of the puzzle is such that it requires active participation from the viewer. In short, the viewer becomes the 'detective' who sifts through the fragments of clues and plot, and the satisfaction derived from the final revelations will be predicated on just how attentive the viewer has been, and how sharp their detective skills are. I don't want to overstate the complexity of the plot, which is actually fairly simple when it's all unfurled (and not unrelated to the two Argento films from which the film takes its title), but there's a satisfaction to be gleaned from figuring everything out which is greater than that offered by a standard gialli, with explanation-exposition which sets everything out in an A-B-C manner.

One final note on the film's shooting style-once the final pieces of the plot puzzle have been slotted into place, one could argue that the disorienting POV shots, and the dream-like atmosphere, are entirely narratively justified. Oh, and the music's pretty damn great too, as with most neo-gialli.

|

|

I've avoided using the n-g term until the end, as in many ways this is an archetypical n-g: idiosyncratic style channelled through the killer's point of view rather than the formerly-de rigeur amateur detective's, a pounding soundtrack, and retro-fetishisation. However, unlike many n-gs, there is an actual, old-school mystery to be solved here, which I'd view as being the distinguishing factor between a pure giallo and a neo-giallo. The film may exist in the farthest reaches if giallo-land, but it does belong there, far away from the neo-giallo ghetto into which so many of its contemporaries have deservedly been banished. By me, anyway.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed