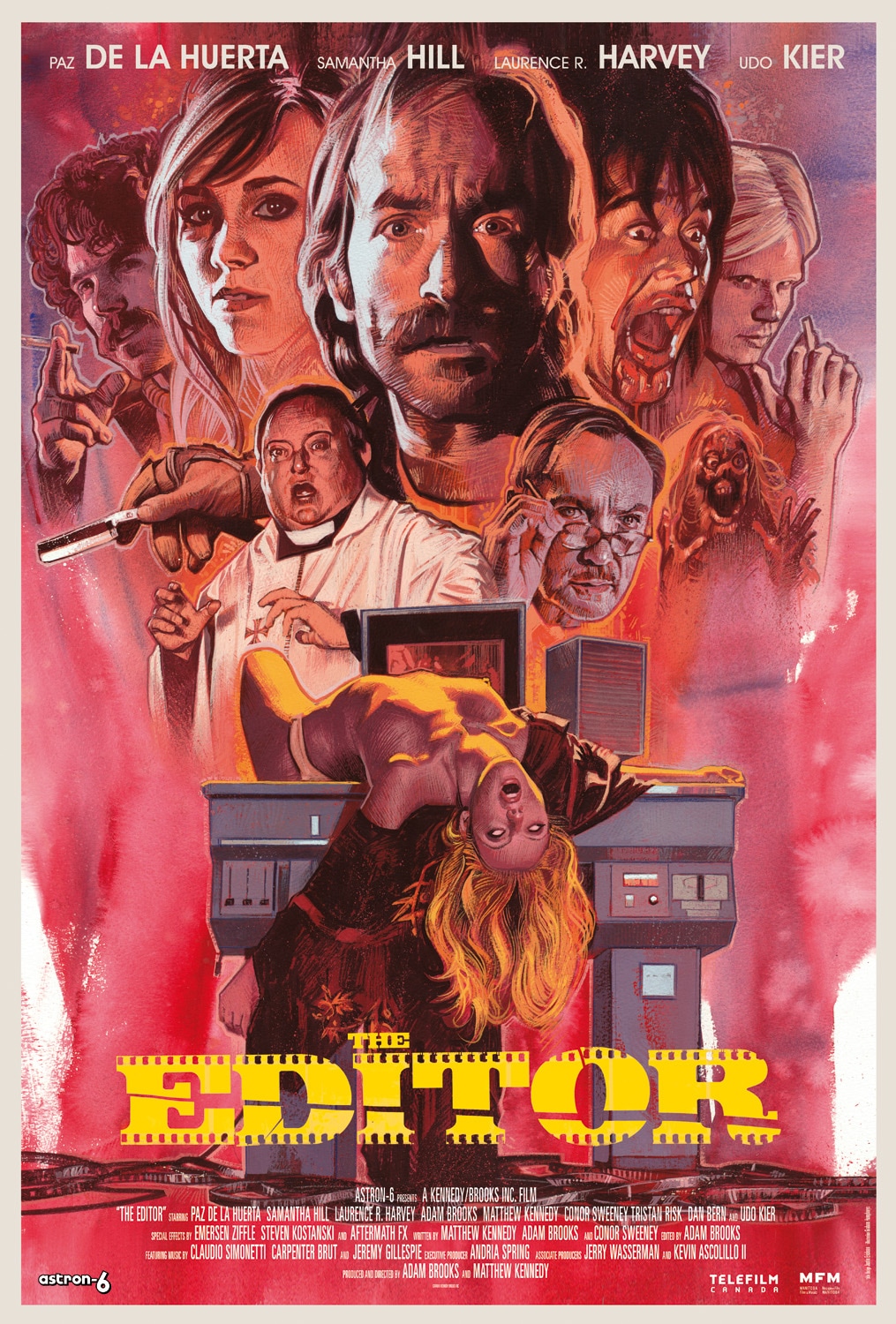

The Editor tracks a film editor, Rey Ciso, and a police detective, Peter Porfiry, as they try to catch a murderer who's slicing his way through the cast of a giallo film on which Ciso is working. The killer seems to be trying to frame Ciso, as each victim has been shorn of the fingers of their right hand, echoing an injury suffered by Ciso himself several years before as he attempted to cut the longest film of all time. There are nods aplenty to classic Italian films (both within and without the giallo genre), and Udo Kier pops up as a creepy (naturally) doctor who runs an insane asylum. After the killer is unmasked (and melted alive) and order is restored, we're treated to one of those twist endings beloved of Italian directors of the past.

The film is a product of the Astron-6 collective, a group of Canadian filmmakers who have also produced Manborg and Fathers' Day, showing a flair for over-achieving on minimal budgets. Interestingly, even though The Editor had by far their biggest budget, it's not much more ambitious in scope than Fathers' Day, which cost less than a tenth as much. Visually, the film's a mixed bag, with as many fantastically-lit sequences as there are shots which are awkwardly composed, with frequent recourse to overly-tight framing, and characters speaking from off-camera, or with only part of their body visible in the frame. Fathers' Day also contains similarly variable visuals, and it's possible that Adam Brooks and Matthew Kennedy, the co-directors, are too idiosyncratic and inconsistent of style to ever make a big commercial breakthrough. That said, The Editor does contain much visual delights for the discerning giallo fan, with the 70s production design, and hair and make-up, brilliantly realised.

As usual with Astron-6, there's very much a tongue-wedged-firmly-in-cheek aspect to proceedings, with visual gags (Ciso getting distracted by the cigarette burn reel change mark appearing), brilliantly-phrased one liners ("a good man holds a beer") and plenty of homages. I've always been suspicious of homages in films, as there's a fine line between paying your respects to a film or filmmaker which has inspired you, and showing off your incredible in-depth knowledge of niche films.

For the most part, the homages in The Editor go beyond merely quoting from other films. Instead, the homage is adapted and reworked, usually for comic effect, occasionally even commenting on the original moment which is being referenced. The best example, for me anyway, comes when Inspector Porfiry is researching a potential occult link to the murders (one of the lesser-realised homages, which amounts to nothing more than an excuse to show a tattered copy of The Three Mothers book). As he sits alone in a dark library, a series of tarantulas begin to slowly approach him. Instead of falling into a Beyond-esque trance as the spiders get ready to attack, Porfiry merely stamps most of them to death, and flicks the remaining one from the desk. This perfectly satirises the static nature of the much-discussed tarantula attack in The Beyond, where a character lies still, apparently paralysed, as tarantulas slooowly approach him, before gradually eating his face off.

|

The mystery aspect of the film is fairly perfunctory, with Porfiry's investigation not really amounting to anything, and his discovery of the murderer happening by accident as he's about to kill an innocent party. Rey's dark backstory, so typical of characters in the genre, is given plenty of airing here however, allowing a visit to the aforementioned asylum, which provides one of the film's creepiest moments, albeit one which is immediately undercut by humour. One gets the sense that Astron-6 use humour as a crutch; a way of insulating themselves and their work from overt criticism-anyone who doesn't like it can be dismissed as not having gotten the joke. And there are good jokes here, lots of them, but at times the complete absence of earnestness does threaten to overwhelm the film. Brooks' and Kennedy's hearts are in the right place, but they're buried, deep down beneath a layer of irony, so thick you'd need an extra-sharp knife to penetrate it.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed