The next morning, Inspector Stacev, heading the subsequent investigation, can't find any evidence of the murder. Each of the sisters, who had all been sleeping with Yuri, accuse one of their siblings of the murder, and attempt to win Stacev over by seducing him. Stacev becomes increasingly caught up in their web of seduction and lies, which drives his girlfriend Irina to suicide.

In a bizarre about-face, the sisters then begin confessing to Yuri's murder, with Stacev no nearer the truth. Eventually, when confronted with photographs of one of his sisterly liaisons, their true motive is revealed: they want to recover a suitcase which was confiscated by the police one week before Yuri's 'murder'.

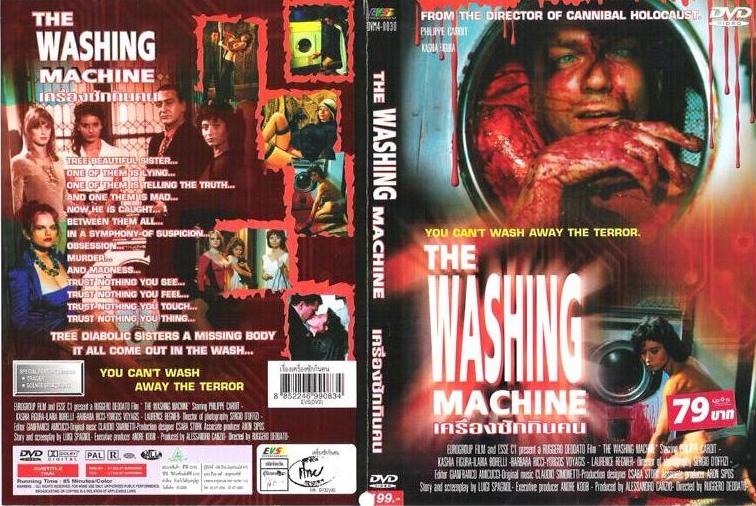

Why am I writing about The Washing Machine, for example? Because it's a giallo, and I write about gialli. Why have I seen Naked Obsession, enabling me to compare it to this film? Because it was directed by Sergio Martino, one of Italian genre cinema's finest craftsmen (pre-1990, anyway). A film can be marketed(/defined) by its content, actors, behind-the-camera talent, and so on. And such trivialities as whether or not a particular film can be considered a giallo can actually make a big difference to its potential audience, particularly on home video. One particularly thorny-for me, anyway-consideration for some giallo fans is nationality.

There are those who maintain that only Italian films can be considered gialli. This seems ridiculous to me, particularly because many of the films themselves were made with an eye on the international market, and used international actors, languages and financing. If the films were closely tied into specifically Italianate social concerns, a la many neo-realist films, then a case could be made for it being part of a national cinema, but they're not. In fact, many gialli are either set outside Italy, or depict foreigners in Italy. At best they're international cocktails with an Italian flavour, and, as with all cocktails, some are more flavoursome than others. And, above all, it seems ludicrous to have to justify why Luciano Onetti's (Argentinian) Frnacesca is at least as much of a giallo as Enzo G. Castellari's Cold Eyes of Fear.

The Washing Machine boasts a largely Italian cast and crew, contains two murders and one suicide (which is dealt with an almost horrific air of casualness); it contains a murder investigation, a loud, driving score, occasional directorial flourishes and maintains a healthy level of eroticism throughout. Its giallo credentials seem pretty air-tight. However, when you see these elements put into action on the screen, the giallo mask (the masked killer, incidentally, being one of the traditional giallo elements that's MIA) slips somewhat. The main characters, who initially accuse each other of committing the murder which kickstarts the plot, quickly start confessing to the murder themselves, seemingly trying to outdo each other in terms of outlandish unbelievability. The investigative plot thus grinds to a halt, the film becoming a sub-sub Rashomon parade of T&A, until these characters deign to unveil the truth. Anyone who's a stickler for narrative logic may also find fault with the notion that a policeman in Budapest would simultaneously work on both the murder and drugs squads.

This flirtation with giallo is nothing new for Deodato, who made several films which hover around the periphery of the genre without ever really striking out for its heartland (Bodycount, Dial: Help, Phantom of Death). The murders (SPOILER ALERT) both take place within the last few minutes of the film, with the original killing, which drives the plot, turning out to have been fabricated. This results in one of my favourite type of twist, with the 'plot' we've believed to have been driving the film revealed to have been the cover for another, deeper plot. Overall, though, what really differentiates the film from any number of North American 'erotic thriller' productions (e.g. Jade, Basic Instinct)? The answer, sadly, is that the film is largely the product of Italian people. So, by covering it here and eschewing its North American brethren, I'm just as guilty as those internet idiots of giallo fascism (not Italian fascism, though; that was more Mussolini's bag).

Unless it's all just cover for another, deeper plot which I've cunningly concocted.

It's not though.

*

Some quick notes regarding the style of the film: it looks much the same as the other early 90s Italian films, with a stark, desaturated palette, although the nighttime lighting is slightly more interesting here than in those Lado, Martino etc efforts. Given that (SPOILER AGAIN) there's no killer at work until the final few minutes, the lack of stalk-and-slash scenes is a necessary evil, so to speak. There are a couple of scenes which feature the nominal lead, Inspector Stacev (this is another internationally-set giallo) creeping around in the darkness, but Deodato doesn't fully commit to either scene in terms of creating a fully-fledged giallo set piece.

The second is thrown away completely, ending almost before it has begun with Stacev lashing out at a mysterious intruder, who turns out to be his (soon to be late) girlfriend. The first is a promising set-up, with Stacev and Vida, one of a trio of sisters at the centre of the film (and 'The Three Sisters' would have been a much better title), searching an abandoned house for clues, with Vida disappearing suddenly, just as the lights cut out. Stacev slowly ascends the stairs, unsure of what has happened to Vida and who or what else may be in the house, before he's suddenly handcuffed to the banister and brutally raped by his erstwhile companion. Although, as is par for the course in exploitation films, because the rapist is a highly sexualised women, it's presented as an act of eroticism rather than one of violence.

The slow ascension of the stairwell is accompanied by Claudio Simonetti's brilliant score, and does threaten to become a properly tense scene. The problem is that Deodato can't resist filming Philippe Cariot, playing Stacev, in a series of stylishly gliding tracking shots and pans as he climbs the stairs. We know that no masked killer (or rapist) is going to jump out at him simply because the shots are too artful, too carefully composed for Deodato to risk upsetting their balance by introducing a wildcard element.

In my opinion, the best way to generate tension in such a scene is to cut down on the number of shots, and keep the framing wide, maintaining or heightening the presence of the location, so that the character's vulnerability and isolation is foregrounded. The location becomes almost a malevolent presence, as we know that its harbouring an actual human malevolent presence. This puts the audience on edge, and a well-timed jump scare can put them over that same edge.

Another tactic is to build up to a clearly telegraphed and choreographed moment. Music can play a huge part here, and there's scope fora greater variety of camera angles and shot selection. Here the tension is derived not from wondering when the attack will come, but from the knowledge that it is coming, whether we like it or not.We're watching a character moving slowly, inexorably, towards their inevitable demise, and there's nothing we can do to prevent it (apart from look away, a tactic which Dario Argento satirises in Opera).

In the case of The Washing Machine, Simonetti's score doesn't quite generate the requisite tension, being slightly too melodic and overused in the film to really set us on edge, and, as stated before, the focus is slightly too much on the glossy technical aspects, with shots selected to look nice rather than to add anything atmospheric.

|

|

The 'attack', such as it is, comes in a shot which focuses on Stacev's hand sliding along the banister towards the camera (frame-left). Vida's hand shoots in from the right hand side, in an effective enough jump scare. The moment is largely unsuccessful, for me anyway, because there is no sense of cumulative tension, beyond that automatically generated by having a man walk alone through a dark house. The isolation of, and focus on. a single, not-especially-vulnerable body part (the hand), also takes the edge of the scene.

Which is maybe not such a bad thing when you consider the extremely edgy rape scene to follow. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed