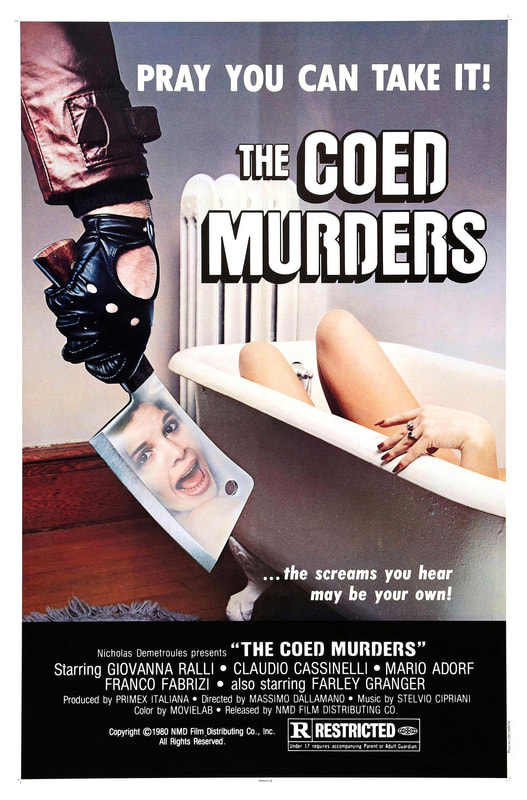

After the nude body of a teenage girl is found hanging from the rafters of a loft apartment, evidence emerges which suggests that she was murdered elsewhere, with the suicide being staged. Commissioner Silvestri of the murder squad takes over the case. Somewhat-assisted by the spunky new (female!!!) DA, he untangles a messy web of underage prostitution which has links to the very top levels of society.

This is a much angrier film than Solange, which viewed the violation of the (somewhat) innocent young victims through a poetic, almost elegiac, filter, occasionally veering off course to indulge in some vigorous perving. Here, there's far less perving: only one and a bit semi-decent nude scenes for you raincoat brigade, unless you're into naked dummies. (Still, the character [if not the actress] in the nude scenes is fifteen, so Massimo hasn't gone and left you empty-handed, so to speak.) There's much more bile in general on display here; Dallamano is clearly fed up of political hypocrisy (if not general hypocrisy; he's still prone to celebrating both the purity and sexiness of young girls), and takes aim at the establishment with one barrel (the other one presumably aiming at an ingenue somewhere).

Anyway, that's enough pervy old man jokes for the moment. This is one of those gialli which takes a slightly different approach to the mystery element. It's also one of those gialli which isn't an out-and-out giallo; there's more than a hint of the poliziotteschi, with the investigation being police-driven, and a half-decent example of the Italian Chase Scene occurring at the halfway point.

The Italian Chase Scene differs from the Hollywood Chase Scene on one major point-permits. Hollywood, in an early example of political correctness gone mad, generally insisted on closed roads and shooting permits for city-based car scenes. Italy notionally did the same, but its directors took a very laissez-faire attitude towards these rules and regulations, even (/especially) when operating overseas. Very, very few of the Italian exploitation films which utilised New York and London for exteriors, for example, would have gone through the official channels to obtain permits. Car chases, which were a staple of poliziotteschi, were usually filmed on open roads, often featuring stunt drivers weaving in and out of several lanes of moving traffic. Just keep an eye on pedestrians in such scenes, and see how often they look around in bewilderment or jump out of the way in a manner which is too natural to be the acting of an extra.

The chase scene in ...Daughters is far from top-of-the-range (compared to, say, the admittedly-plot momentum-destroying one in Strange Shadows in an Empty Room), but it's not bad, and features some nifty in-car footage. The lax Italian attitude to safety would come back to haunt lead actor Claudio Cassinelli, however, when he died in a helicopter crash while filming Hands of Steel in Colorado. Ironically, it's quite likely that the production did have shooting permits, as an article in the Chicago Tribune stated that the crew had been based in the same location for ten days. Also somewhat ironically, possibly the most celebrated American car chase, from The French Connection, was in fact filmed sans permits. This somewhat negates my above ramblings, so I'll move on.

The car chase is preceded by a chase on foot down a hospital stairwell, which is actually far more exciting and dynamic, and also features an excellent surprise-hand-chopping-off. The music for this scene is bizarrely chilled, and lacking in any urgency, but the staging and camerawork almost make up for this. There's also a classic underground car park chase scene which, upon rewatching, I can see bears a surprising amount of similarities to a chase sequence in my own Three Sisters. It was surprising to me, anyway, as I didn't realise I'd ripped off the film quite so closely (and worsely).

As I mentioned earlier, this film doesn't contain a typical guess-the-killer plot. It does, notionally, but the guilty party is not a character who we've come across previously. Although, saying that, the killer isn't the real baddie here-he's pretty bad, sure, but he's merely a puppet being manipulated by more powerful figures, from the upper echelons of society. We do see some of the less-important powerful figures, but the real top brass, ie the most guilty parties, remain off-screen. Thus, the real villain takes on a less-human and more-conceptual bent. It's not any one killer who's responsible, it's a system which has strained and broken under the weight of power.

There is a minor mystery revolving around the identity of a voice on a recording, the solution to which isn't overly dissimilar to the major 'eureka' moment in other gialli (eg Bird With the Crystal Plumage), and there's a classic 'switcheroo', where a dead character is claimed to be alive in order to flush out the killer. The tropes of the giallo are alive and well here, then, they're just serving a more complex, and political, story* than is the norm.

To return, then, to the issue of the female. Dallamano gives us, on paper at least, a female protagonist here with the top-billed Giovanna Ralli. She's continually having to assert her status as a(n assistant) District Attorney, in what was likely an all-too-accurate representation of Italian society in the early 70s (and the late 2010s). She's a far more independent, and less idiotic, character than Karin Baal's in Solange, but she actually contributes little or nothing to the investigative cause. She becomes a damsel in distress for the underground car park chase, and otherwise spends most of her time correcting people who assume she's a secretary, or that the (assistant) DA must be a man. Dallamano seems to be trying to make a point, or at least rebuff some prior criticism, here, but he can't quite see it through.

Then there's the thorny issue of the schoolgirl hookers. If Dallamano really wanted to light a candle for the (alleged) 8000 youths who went missing every year, he sure chose a strange way to go about doing it. The girls here are all from loving, middle-class homes (which can afford to send them to expensive therapy), and aren't runaways. The girls, too, possess that curious mixture seen in Solange: they're young, and therefore somewhat pure, yet they're also marked by deviant (/human) sexual desires, as evidenced by the way that all of them seem to be initially quite enthusiastic about becoming prostitutes. Their burgeoning sexuality is thus bringing about their ruin, even if it's the very thing that clearly simultaneously fascinates Dallamano. It'd be a lot easier if all girls just remained prepubescent, he seems to be saying, like the two girls whose attentiveness (presumably due to their not being distracted by, or distracting to, sexual urges) leads to the eventual apprehension of the killer. Then again, even prepubescents aren't without sin, as he'd later show us...

This isn't half as beautiful a film as Solange, either visually (come back Joe d'Amato!) or thematically. It's bristling with rage, though, even if it's sometimes a contradictory rage which can't quite figure out what it's angry about. Ultimately, though, it seems to be saying that we are all just pawns, at the mercy of darker, inhuman forces. The climax reminded me a great deal of the scenes midway through The Dark Knight, where the police track down the sniper who shot at Commissioner Gordon. Just like in this film, there the sniper was but a pawn being manipulated by something far more sinister (The Joker). Unlike here, though, Christopher Nolan didn't focus his attentions on a plot strand about underage sex which in some ways has nothing to do with the apparent point the film's trying to make. He did have that scene with the people on boats, though, which is almost as bad.

|

|

*One flaw in said story is the apparent staging of a character's funeral within an hour or two of the discovery of their corpse. I know Italians love any excuse to indulge in an aul' mass, but this seems to be a tad unrealistic a timeline.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed