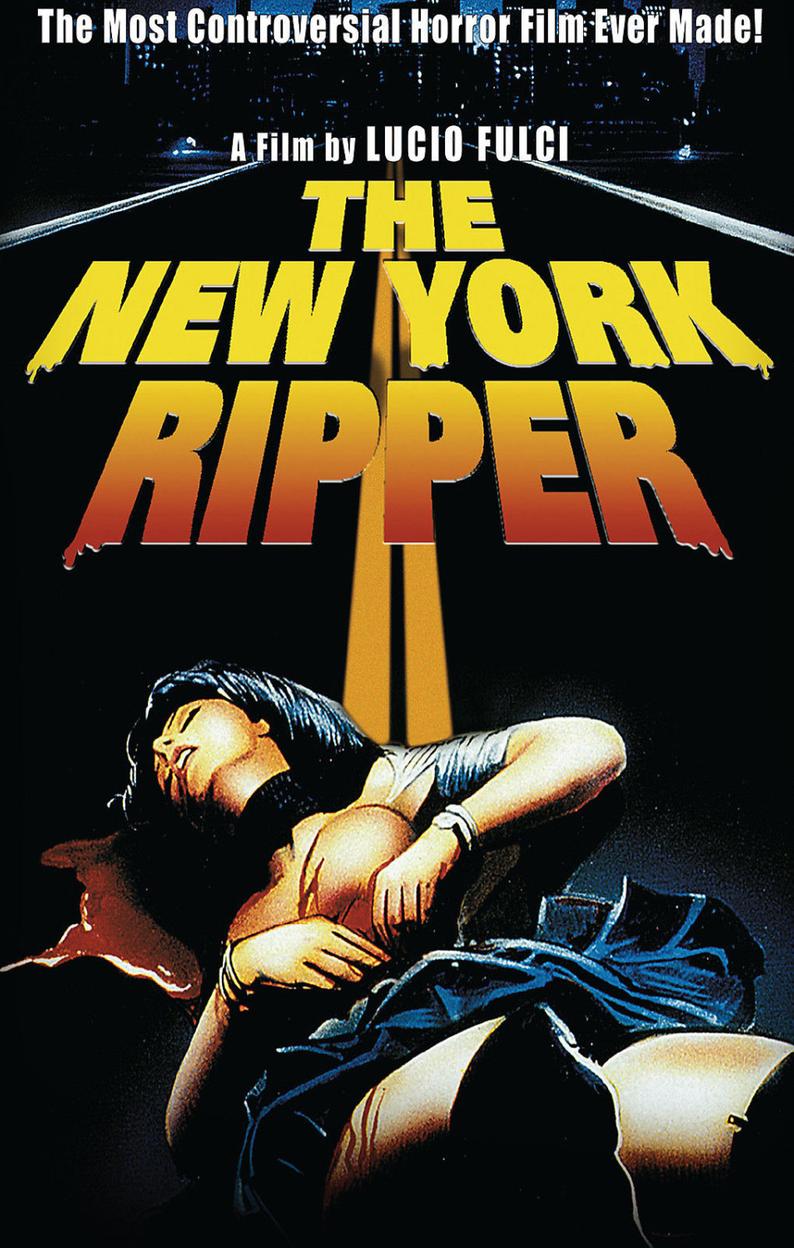

A killer who speaks in a voice which was blatantly ripped off for Itchy off The Simpsons is ripping his way around New York. Given the fact that the police investigation is being led by one of the Worst Giallo Cops of All Time, Jack Hedley's Lieutenant Fred Williams (probably not named in honour of the somnambulistic star of Vampyros Lesbos), the ripper manages to cut quite the swathe before any progress is made towards catching him. After one of his intended victims escapes alive, the police think they've a positive ID on the killer: Mikos Scellenda, a Greek pervert who attempted to molest the woman shortly before the killer struck. Dr Davis, a psychotherapist attempting to profile the killer for the police, doesn't believe Scellenda is the killer, and, given there's still half of the film left, we can be pretty sure that he's right. Who is the killer, though, and why do they speak in that crazy duck voice?

First thing first, I'll get straight into it and discuss the big M(isogyny). Having had that term used as a stick with which to lightly beat one of my own films, I think I'm well qualified to speak about it here. So, is The New York Ripper a misogynistic film? Was Fulci a misogynist? Am I? (I'm not; the idiot woman reviewer was wrong.) Fulci himself may well have had some slight issues with women, although it's extremely dangerous to extrapolate such observations solely based on viewings of his films and the opinions of those who've worked with him. And, anyway, a misogynist mightn't necessarily make a misogynistic film.

By the same token, a misogynistic character doesn't automatically mean that the film endorses said character's opinions (YOU HEAR THAT, GILLIAN MIDDLETON? [I jest, you're alright]). The killer in this film undeniably hates women, but the film itself doesn't really row in behind this viewpoint. There are several murders of women, sure, featuring varying degrees of graphic violence, but the fact that the film is specifically about a man who hates, and kills, women necessitates this. And, given that it was a commercial film, and one made by a director garnering increasing fame for his graphic violence, the kills are of course going to be full-on.

However, it's important to remember that a full-on murder depicted on screen is just that, on screen. One of the gorier deaths in my own giallo The Three Sisters featured the murder of my own mother. Do I want to kill her in real life? Of course not, I want to kill my father (not really, I'm jesting again [and anyway, he did die in the film as wel]). She was just a reluctant actor playing a role in a film, the plot of which happened to require her on-screen death. Of course, I did come up with the plot, and could have come up with one which required fewer female deaths, but I didn't. However, in my first film, The Farm, far more men than women die on screen. Again, I could have come up with a different plot, etc etc. My point is that a film depicting women getting killed isn't automatically a misogynistic tract.

To get into more specific NY Ripper-related discussion, one of the main arguments in favour of it being misogynistic is the depiction and treatment of Daniela Doria's prostitute, Kitty. She's only fleetingly in the film, and spends her entire screentime nude. The camera never leers at her, apart from arguably during her death scene-although any leering there has more to do with highlighting special effects-but confining a prostitute character to essentially being defined by her profession, and depriving her of any clothes, isn't necessarily the most progressive depiction of a woman. Saying that, that does inherently assume that there's something degrading or shameful about the female body, which shouldn't really be taken as a given.

Another area of controversy is the character of Jane, played by a supposedly 25 year old Alexandra Delli Colli (I only note her age because she's so patently older than that; not as an attempt to shame her-she still looks very nice!). She's something of a voyeur/exhibitionist, her sexuality contrasting with her voyeur/impotent husband, who tolerates-and even encourages-her sexual adventures. These adventures encompass a peep show, a deeply uncomfortable encounter with some Hispanic guys in a bar, and a sexy hotel rendez-vous with Mickey Scellenda. She ultimately pays for her licentiousness-as traditional society would no doubt view her behaviour as being-when the Ripper knifes her to death after she escapes Scellenda's eight-fingered clutches (that's just me saying that he has only 8 fingers, it's not a description of some kinky sexual act).

It's tempting, and easy, to read her demise as a punishment for her perversions/sexual adventurousness, but equally she could be viewed as a victim in a male-dominated world which isn't yet ready to take female sexuality seriously. Whether or not the film falls prey to this inability to properly respect her sexuality is unclear (course it is-I've been banging on about this exact thing for several paragraphs now), but the fact that she gets sexually assaulted in a bar and still goes out on potentially dangerous night-time hook ups doesn't necessarily mean she deserves what she gets (of course), nor does the film necessarily endorse this.

To take a small lateral step, the pornography which is in abundance in Scellenda's apartment would seem to suggest a parallel being drawn between an obsession with sex and general deviancy. He doesn't seem to have any extreme porn, yet he clearly likes the stuff, and we know that he's into kinky sex, and not above trying to molest women on the subway. In short, he's a bit of a shit. But is everyone who likes porn as much of a shit as he is? Dr Davis, for one, likes porn (albeit of a more homoerotic bent than Scellenda), and while he does come across as a self-satisfied asshole, he's not a deviant killer. Is the short scene of him buying the gay porn mag designed to suggest that he may very well be such a monster, only for his ultimate innocence to show up such inferences as being inherently prejudiced? But then, does the film itself invite such prejudices by highlighting the gay porn-buying?

My point here is that these things aren't black and white; the film is neither inherently misogynistic nor inherently progressive. Like the fever dream at its centre, which begins with Scellenda's attempted assault on the train, the truth is more elusive than it first appears. It's probably easier to find evidence of the film being misogynistic than not, but that doesn't mean that Fulci isn't loading it with more nuance and intelligence than for which it's often given credit. And there's a level of self-awareness suggested by the early exchange between the young cyclist and the driver of the car in which she's ultimately killed (where the hell is the driver when the ferry docks, by the way?), in which he rants at her to get back in the kitchen, to suggest that the film was consciously creating a space within which to interrogate misogyny. And I've certainly taken my cue from that here.

To change tack completely, it's worth detailing just how poor a detective Jack Hedley's Lieutenant Williams is. He discounts the aforementioned car driver as a suspect for the cyclist's death due to a perceived lack of physical strength (which the ultimate killer doesn't seem to possess at all), despite the fact that she was murdered in his vehicle, and he was suspiciously absent at the time of the body's discovery. Previously, upon hearing that the ripper's first victim was overheard on the telephone making arrangements to meet a strange duck-voiced caller, he immediately dismisses the witness without asking where or when the rendez vous occurred. He claims that the killer is 'maybe... between 28 and 30 and has lives all his life in New York' after the second killing, an outrageous series of assumptions that are based on Nothing Whatsoever.

And, most seriously of all, he's indirectly responsible for the death of Kitty, his prostitute girlfriend, because he's so obsessed with locating a phone booth from which a call is being made that he ignores the fact that the killer explicitly told him that Kitty will be murdered shortly, which suggests-especially given the film's confining her to a single location-that it might be better to go straight to her apartment. Or at least to send one of the plethora of police vehicles to check on her, instead of bringing them all to one location. Is it his professional pride that prevents him from disclosing her location sooner, given his relationship with her, or is he really just that limited brainwise that he couldn't think beyond tracking the call?

Williams flits in and out of the narrative, as do all the 'lead' characters, which is indicative of the rudimentary narrative which doesn't really have a strong through-line. The film is very episodic in nature, much as Fulci's gothic horrors of the time were, with a seedy 42nd Street atmosphere* replacing the more oblique, supernatural vibe of those other films. The attempted murder/dream sequence which lies at the centre of the film does capture the disorientating feel of something like The Beyond, with the moment when the killer reaches under the cinema seat to grab the woman being particularly effective. The audio of this scene is terrific as well, even if the musical choices which accompany several of the stalk-and-slash scenes are idiosyncratic, to be polite. And what's with the Italian movies' belief that New York is a city of incessant horns, both of the car and ship variety?**

In terms of being a successful giallo, the film falls undeniably short. The mystery aspect is curiously handled, always towards the centre of the film but never really being afforded the respect it deserves. There are shockingly few suspects (especially if we take a leaf out of Williams' book and discount the car driver); possibly two, and at most three. The aforementioned dream sequence (SPOILERS) depicts the killer as the killer, with the revelation that it was (supposedly) just a dream being presumably intended to lead to us naturally directing our suspicions elsewhere-we've strongly suspected this character for a few minutes before his apparent innocence is revealed, and logic suggests that the actual killer in these films never assumes the role of suspect. This is an interesting-if not exactly totally original-approach to take, albeit one which would work better in a film which is more concerned with plot. Overall, plot certainly takes a back seat here to the sex, drugs and funky jazz music. And-whether you like it or not-to the killing of lots of nudie ladies. But still, if there's one thing that True Crime series can teach us, it's that women love to consume stories about women being killed, so maybe Fulci has made the most female-friendly film of all time.

He hasn't, though-he's made an incredibly powerful, angry film which, just as in something like Last House on the Left, is all the better and more shocking for containing such passion. Just be aware that you're unlikely to skip out of the room after seeing it, as it literally contains the most depressing and nihilistic ending ever. But don't skip out of the room anyway, you're not six years old. And if you are six years old, please Christ do not watch The New York Ripper.

*To briefly return to talking about sex, I believe that the extremely perfunctory backstage interaction between Zora Kerova's sex show performer and one of her co-workers can be seen as being more significant than it might first appear-after seemingly climaxing onstage in paroxysms of delight, Kerova's disinterested shrug when asked how it was pulls back the metaphorical curtain to reveal the often performative nature of sex. Even though she performs a physical act with literally nothing to hide her body, the depiction of sex offered up to the audience is not authentic, much as the copious sex scenes in the film are being performed by actors. It also highlights how depictions of sex and sexuality are often dressed up to appear as more exotic and exciting than they really are, which can fuel resentment in people of the same mindset as the killer. So, while far from everyone who consumes pornography is a deviant killer, there is [erhaps something potentially dangerous in the selling of unrealistic dreams to downtrodden people.

**To be fair, I've never been there and the filmmakers have, so they may be right.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed