Alessandro Marchi, a television presenter, is arrested for the murder of a young girl, who was a friend of his daughter. After calling into question the accuracy of the witnesses who allegedly saw him fleeing the scene of the crime, as well as the veracity of incriminating circumstantial evidence, his lawyer plays the defence's trump card- Marchi, who had previously claimed that he was aimlessly walking the streets at the time of the murder, was in fact with his mistress. After it transpires that the mistress has gone on holidays, and after slightly implausibly refusing to either try and locate her or wait for her to return home, the court sentences Marchi to life in prison. We then find out that Marchi's wife and lawyer are having an affair, while his daughter has recently kindled a romance with Giorgio, a disaffected young man from a privileged background.

After two more women are murdered in an identical fashion to the first victim, and Marchi's mistress finally returns from her holidays to confirm his alibi, he is released. After sheepishly being reunited with his wife, he discovers the truth about her affair, and the two of them spend a lot of time staring at each other and then the ground. He then gets a phonecall which is apparently from a blackmailer ("Hello?... Blackmail?!"), and goes to an isolated warehouse. Giorgio is there waiting for him, and he reveals that he killed the second and third victims in order to precipitate Marchi's release. He explains that he was the lover of the first girl murdered, and he wants to take revenge in person. Marchi admits that he did kill her, after she spurned his advances. They fight to -literally- the death.

The film replaces this investigation with an extended examination of police methods, and indeed a police forensics team seem to be thanked in the film's end credits, if my Italian is up to scratch (it isn't). These ultimately bear little relevance on events down the line, apart from forming part of the case against Marchi, but, especially given that the main protagonist isn't a policeman, the degree of detail present in these scenes is highly unusual for a giallo.

The main protagonist may not be a policeman, but it's open for debate as to who or what he or she is. The film jumps around among the main five or six characters, treating them as effectively equals, which denies us the typical identification figure offered up by most gialli, upon whom we rely to navigate through the narrative's twists and turns. As I've already stated, much of the 'plot' of this film has taken place at or before its start. This in turn leaves more room for 'character' to flourish.

Speaking (very, very) broadly, the two main ingredients in any commercial film are plot (what happens) and character (the people to whom it happens). They are present in differing ratios in different films, with some favouring breakneck plot developments with very little emphasis on character (eg North by Northwest) and others preferring to focus on interrogating the psyche of the main character/s over and above furthering the plot (eg There Will Be Blood). Camerawork, sound design, costuming, score, editing etc are used to enhance plot and character in differing ways. Plot and character are also not mutually exclusive, and can simultaneously exist in a single moment, eg Tom Cruise's first kill in Collateral kickstarts the film's main plot, and simultaneously establishes him an a hitman who has planned everything meticulously.

Most gialli feature 90% plot, with the 10% character being used to create suspicious backstories for the various red herrings, and then to explain the murderer's motive. The lead characters are often little more than cyphers (this isn't necessarily a bad thing; most Hitchcockian leads could be said to be the same). The Bloodstained Butterfly, due to its unconventional structure and its lack of an obvious lead, allows its characters more room to breathe than most other examples of the genre, going so far as to allow Giorgio and his father indulge in an extended conversation about class politics (which almost feels like it's ripped from a Fernando di Leo script). The familial politics of the Marchis are also given extended reign, with the daughter's evident disdain for her (adoptive?) mother, and affection for her father, evident. She and Giorgio also have a sex scene which does little to advance the plot, and functions almost as a inverse reflection of the classic rape-turning-to-enjoyment scene (eg Straw Dogs), with Sarah Marchi becoming ever less enthusiastic as Giorgio essentially goes mental, and gurns until he can gurn no more (and has orgasmed).

These character asides turn out to have direct relevance to the plot, as Giorgio, who grows increasingly manic over the course of the film, is revealed to have been tormented by the death of his lover, which has in turn affected his behaviour. In another example of character informing plot, we see that Sarah's obvious closeness to her father (with incestuous undertones) gives him the opportunity to grow close to her friend, leading to his unsuccessful, and ultimately fatal, attempted seduction.

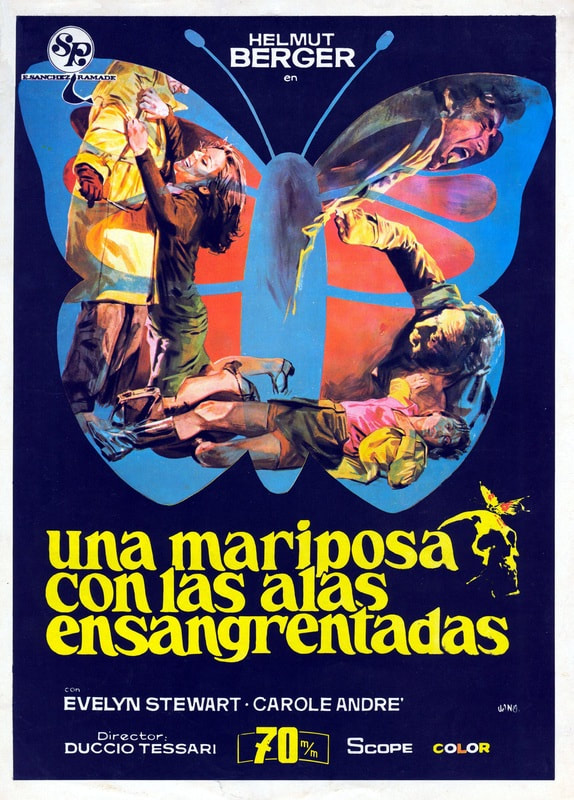

The plot kicks into overdrive in the film's final scene, with the big reveal as to the killer's identity (actually identities). The clever twist of there being two killers who were not working in tandem (also used in Argento's Tenebrae, and to ludicrous effect in Bay of Blood with its multiple murderers) is a clever concept, and is essentially unguessable from the perspective of the audience. Giorgio's being one of them would appear to be slightly problematic however, in that he's been portrayed as being increasingly manic, and is played by the creepy Helmut Berger. It's possible that we're meant to see this as the film overly emphasizing a red herring, and thus dismiss him as a suspect. It's possible that we're meant to automatically dismiss him, as flashbacks early on suggest that he was with Sarah Marchi at the time of the first murder, however it's strongly hinted that the testimony which led to this flashback has been fabricated or embellished.

Even the revelation that he was in a relationship with the first victim- Sarah Marchi's friend- has been heavily foreshadowed, as he leans forward and screws his eyes closed after Sarah mentions that her friend had a secret boyfriend who lived close to him (the Tchaikovsky-influenced soundtrack also swells to a crescendo at this point). It's debatable as to whether we're supposed to ignore Giorgio as a potential killer due to our knowing that he was supposedly otherwise-engaged at the time of the first murder, or due to his blatantly suspicious and deranged behaviour (if you find yourself trapped in a giallo, keep making shifty eyes and you'll quickly be discounted as a suspect). Either way, the end reveal works in a less satisfactory way than an out-of-left-field zinger reveal, but it does work. His motives, it must be noted, are slightly shaky, as he essentially commits murders to bust a guilty man from jail.

That Marchi is guilty is a twist which is made possible by the film lying to us (in the form of a flashback based on his mistress' exonerating testimony). This was done as far back as the late 40s in Hitchcock's Stage Fright, and is a fairly controversial tactic to adopt. Audiences do tend to swallow whole any utterance made by characters who aren't obviously evil, which is eminently exploitable from a writing and directing standpoint, but lying through flashback is a dangerous game. As is killing kids and hookers, as Giorgio and Marchi find out.

One further thing to note is the film's visual style. Duccio Tessari (who made one of the best westerns ever in The Return of Ringo) manages to keep the courtroom section from ever becoming stodgy (when plot and character come up short, fill the void with Style). The 2.35:1 frame isn't necessarily exploited to its fullest, and indeed some compositions can seem a bit cramped, but the camera movement and the staging of the action is beautifully judged. The opening credits (which are worth a rewatch straight after seeing the film) are also very well done, and introduce the characters in a Nicolas Winding Refn-esque manner (titles appear with the characters' names and relation to one another). That the final two characters introduced, Giorgio's father and mother, barely play any role in the film is nothing less than a masterstroke of misdirection, which left me fully expecting one of them (specifically his father) to play a large part in the denouement. That they are specifically Giorgio's parents, and not another character's, is of further significance. The 'character' of Giorgio's father, by virtue of his behaviour in his limited time onscreen, and the very fact that he is his damaged son's father, intersects with the 'plot' of a killer on the loose, to produce a perfect red herring.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed