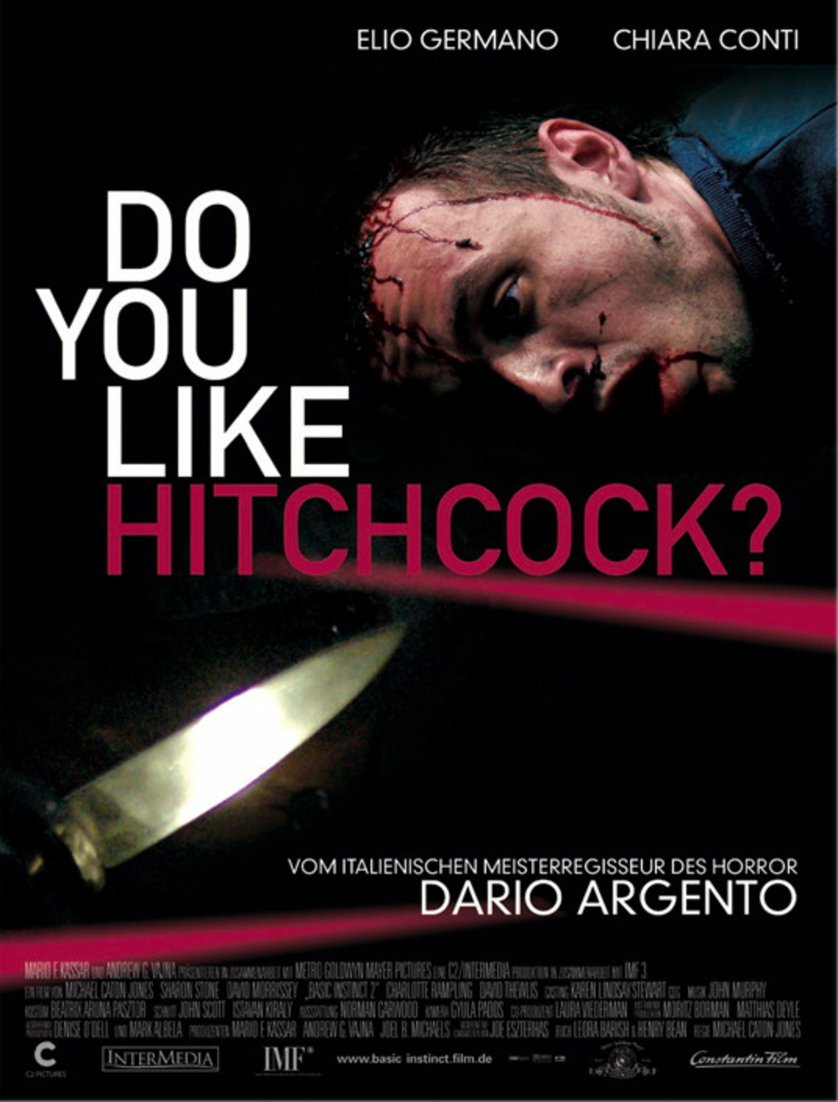

After a vaguely Suspiria-evoking prologue featuring young Julio spying on, and being chased by, two lesbian witches in the woods, we jump forward to mid-noughties Torino, where grown-up film student Julio continues to be a peeper. He also conveniently lives right across the street from Sasha, a vampish young woman with a proclivity for getting undressed, then dressed, then undressed again in front of wide open windows. After Sasha's mother is killed, Julio begins to suspect that her daughter has entered into a Strangers on a Train-esque pact with Federica, a mysterious blonde. Federica and Sasha met at the local video store, observed (of course) by Julio, when both tried to rent the aforementioned Hitchcock film. Julio's obsession with proving Sasha's guilt begins to jeopardise his relationship with Arianna, a fellow student, before his very life comes under threat.

While far from full-throttle Argento, this film isn't without its plus points. The narrative, largely constructed by threading the plots-or, at least, an awareness of the plots-of Strangers on a Train and Dial M For Murder through the prism of Rear Window, holds up on its own two feet surprisingly well. In fact, Argento and co-writer Franco Ferrini almost do too good a job at constructing an extremely neat narrative; an extra twist at the end, or even an oblique digression or two, wouldn't have gone amiss.*

While it may be neat, the plot isn't exactly the most ingenious, and the chronic lack of suspects offered up means most mystery-literate viewers will have cracked the case long before Julio. Usually I'd point to the fact that protagonists in gialli aren't aware that they're characters in a contained cinematic universe, and thus don't know who has been presented to us viewers as suspects, to excuse any sleuthing shortcomings. In other words, as far as they're concerned, anyone at all, even someone they haven't met, could be guilty, whereas we need only choose from anyone in the cinematic world who has registered as a notable presence on screen. Here, though, Julio's focus is actually too narrow; his obsession with Hitchcock's films leads him to conflate the two girls with characters in Strangers on a Train, and he is incapable of looking beyond them as potential suspects.

Anyway, that analysis was leading into a bit of a cul-de-sac, so we'll park it there. As I said, this is far from vintage Argento, and is actually a made-for-TV movie, albeit one of probably higher quality than any of the theatrical features which followed this. The body count is low, with only one bona fide giallo murder, the emphasis instead being on low-octane, tongue-vaguely-in-cheek suspense sequences faintly evocative of Hitchcock's work. It's a fun watch on first viewing, but doesn't overly hold up thereafter. The dialogue is as shonky as you'd expect from late-era Argento (to be fair, it didn't always sparkle in Hitchcock's films, so you could make a very tenuous claim for that being a homage too), and the English dub tends to favour distractingly cockneyed accents.

Before I finish, I'll touch on a couple of giallo-and, indeed, murder mystery-tropes employed here by Argento. The first concerns the cinematic tail. This is not an animal tail, rather it is the act of following someone covertly. I say 'covertly', but time and time again, our heroes and heroines very much follow a hidden-in-plain sight approach to their stalking. I mean, tailing. The apotheosis of this can be seen in Brian de Palma's body double, in which Craig Wasson may as well hold up a big sign reading 'Don't mind me, I'm just following you'.

Here, Julio's attempts to tail Federica, whom he suspects of murdering Sasha's mother, initially involve him sitting outside her office for a full day. And when I say 'outside', I mean directly outside, right in her line of sight. She helps his cause by doing that classic cinematic trick of looking everywhere but at him. He then repeats the trick when he follows her to her apartment, only for her boss, who is blackmailing her for sex, to finally take the bull by the horns and look directly out a window, seeing Julio standing right there watching them. I understand that a realistically covert tailing sequence might be less overtly cinematic than one wherein the director can comfortably keep the tailer and tailee in the same shot, but the bounds of credulity can only bend so far.

The second trope is the off-camera beckon. If you're ever alone in a house with someone and are summoned by them to a different room, make sure they've appeared on screen when issuing the invitation. If they haven't, and have been reduced to a disembodied voice issuing a matey invitation, run for the hills! The reason for not showing the person when they utter that specific line is often because they're engaged in an activity, or sporting accessories, which would immediately mark them as a killer. Thus, they're kept off-screen to delay the unveiling, and hopefully combine the revelation with a jump scare. The problem is that familiarity breeds familiarity, and anyone who is shocked when a seemingly benevolent off-screen invitation turns out to have been uttered by a killer is either young, unfamiliar with horror films, or very, very stupid. In the case of Do You Like Hitchcock?, there's actually no reason why the inviter couldn't have been shown on-screen, as nothing they're doing or wearing would initially give the game away. By keeping them resolutely off-screen Argento sadly blows the one major twist of the film. In his favour, though, he tries to make up for it with a surprisingly lengthy and grisly attempted drowning sequence (which is slightly tainted by the inefficiency of the attempted drowner).

So, overall this film is nothing special, certainly not when held up against early Argento. It's not terrible, though, and has an air of knowing which the more generous viewer could offer up as an excuse for such failings as those detailed above ("He was taking the piss out of lazy stalking scenes, and highlighting how obvious and overused the 'off-screen shout' twist is"). The problem is the generous viewer would be wrong to do that; this film was made as Dario's decline began to increase both in speed and magnitude. Treasure it for what it is, though: his his last kind-of-good film to date, and likely to be his final kind-of-good film ever.

*One climactic twist, of sorts, is the bizarrely twisted logic employed by Julio's girlfriend Arianna to justify her Grace Kelly-esque expedition to confront the killer in the apartment across the street. Even though the police have been notified and are on their way, she claims that they'll need a witness to confirm the identity of the killer, and thus presses on with her mission. It's unclear how exactly her being murdered will make her any more of a witness than Julio, who has already ID'd the killer from his vantage point across the street.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed