After agreeing to take a new hallucinogenic drug so the effects can be documented by a magazine, Valentina has visions of the murder of a wide-eyed young woman by a camp-looking older man. She begins seeing the camp man everywhere, and tries to get the police to intervene. They, as well as seemingly everyone else, seem to calmly accept that Valentina has had a vision of a six month old murder, but refuse to accept anything else she tells them, even when everything else she tells them seems far more credible. Another, slightly (only slightly) less camp-looking man also begins following her, trying to warn her that she's in danger (she knows, man, but no-one will listen to her, apart from the bit about her crazy vision!). She's taken to a mental asylum to meet the man convicted for the six-month-old killing she's apparently witnessed, who turns out to be not camp in the slightest. The bodies continue to pile up, even if, still, no-one will listen to Valentina. Not even her sometime-lover Stefano nor her flirty friend Gio. Will anyone believe her before it's too late? And will she unravel the tangled web into which she's unwittingly stumbled while she's at it?

First things first-I should stress that the 'vision' which Valentina has while under the influence is indeed genuine, although it doesn't necessarily depict exactly what everyone assumes. In some ways it prefigures Lucio Fulci's The Psychic, which places a vision in an even more prominent position in the plot. To enjoy either film, you'll need to buy into the concept of second sight, or else you may as well not bother watching. (If you're someone who watches these films to scoff, you can fuck right off.) It's strange to think that the script, and plot, here are the work of Ernesto Gastaldi, who likes to paint himself as the grounded-in-reality alternative to Dario Argento's tricksy, sleight-of-hand brand of gimmickry. There's no sleight of hand here, I suppose, but interrogating the reliability of memories is hardly more outlandish than a hallucinogen bringing on a psychic vision (not that Argento was averse to indulging in a bit of psychic bantitry).

That leads me on to one further caveat-the film does sometimes come across as being conceived of by old fuddy duddies, who regard drugs as dangerous, unknowable things which bestow outlandish powers upon their abusers. There's an undeniable fascination with the seedy glamour of the lifestyle, as seen in the scene where Valentina attends a weed-and-possibly-opium-fuelled party, but the characters are extremely quick to expound upon the dangers of evil, evil drugs.

Anyway, onto the film itself. It's another long one, which takes a slightly different approach to the more languidly-paced High Heels. Here, the twists and turns come thick and fast, but ultimately this becomes a weakness. High Heels contented itself with a few key twists, and the second half in particular gave the film time to breathe (to the point where, as noted in my review, your mind may wander and solve the case before the police). Here things are a bit breathless, and when almost every scene contains a bit of rug-pulling, you eventually become so dizzy that you're in danger of tripping yourself up. Then you might wee your pants in the shock of the moment, and your entire class will laugh at you and call you 'Pissy-pants' for the rest of the year. But yeah, this is basically a convoluted way of saying there are too many twists here, and each one is slightly devalued as a result.

Saying things in a convoluted way is quite apt, the plot of ...at Midnight being quite the convoluted beast. It's one of those ones where almost all of the characters are guilty to some degree. In High Heels, you get a sense of a wider world in both Paris and the English countryside, with new characters regularly introduced throughout the entire film to support this sense. Here, although a few newbies do pop up as things progress, you get the sense that you're watching things unfold in a hermetically-sealed world, where only the film's characters really exist. Such is the omnipresence of several of the supporting cast that you begin to suspect that Valentina must have a tracking chip implanted somewhere. It's also possible that the city setting hurts the film a bit in this regard; we're more likely to buy the idea of the countryside being full of oddball red herrings, and it's also easier to keep tabs on someone in a quaint village setting.

Re: the pace of the twists and turns, given the eventual explanation the film offers up as the solution, you could argue that the breakneck speed is necessary, as you're more likely to have forgotten characters and events which aren't quite wrapped up in a neat little package by the Big Reveal. You might, for example, wonder how three people managed to gain access to a certain apartment towards the end of the film. You might even ask why Valentina has been targeted by a certain gang at all.

One final semi-criticism-once again, the film's length does lead to a slight dissipation of tension as we approach the finale. This isn't helped by moments such as when Valentina sees three crucial, and evil, characters in an apartment directly opposite hers and tries to phone the investigating police inspector, despite his repeated refusal to believe anything she says. When she's informed by a comedy copper that he's not in the office at that moment, she essentially sighs, shrugs and shuts up. Why wouldn't she be desperate to tell anyone from the police about the killers who are, at that moment, metres from her? It's not as if she'd encounter any more scepticism than she's already guaranteed to get from the inspector. Not only that, she seems to half-forget about the killers, not bothering to look out her window again after initially spotting them. It's as if Ercoli (/Gastaldi) knew that there was another talky scene coming up before the finale proper could get going, so he doesn't bother trying to wring any suspense from this Rear Window-esque set up.

But enough grousing. This is still a superior giallo in almost every respect (music being the only below-par aspect for me; Stelvio Cipriani having been replaced here by Gianni Ferrio). Once again Ercoli directs with a kind of contained flair which only occasionally grates, and even then it's usually because of slightly dodgy camera operating (this only occurs once or twice, so don't let this put you off a viewing). His penchant for half-obscuring characters' faces in close-ups, particularly when they're being a bit nefarious and tricksy, has returned from High Heels. It doesn't quite work as well here, possibly because there are fewer close-ups in general and the arty ones thus seem a bit shoehorned-in.

The killer (the main killer, anyway) has a great look as well. I referred to him as being 'camp-looking' above, and this is very true, but it's creepy camp. He looks like a slightly more evil version of Andy Warhol or Paul William's Swan from Phantom of the Paradise, and he has a terrific run (more of a trot really). There are liberal shots which take advantage of the reflective nature of his sunglasses, suggesting that Ercoli (/Gastaldi) has been watching The Strange Vice of Mrs Wardh. Gastaldi's certainly been watching it anyway; he wrote it, and seems like the sort of man who wouldn't be averse to watching his own films. It's often difficult to maintain a sense of menace when you see a killer as a whole person, rather than a series of disembodied close-ups (something I touched on when writing about The Cold-blooded Beast), and here Ercoli very much succeeds. The hired goons who turn up near the end also have a great look, especially Luciano Rossi. Maybe the key is to combine an impassive face with sunglasses, which both characters have in common.

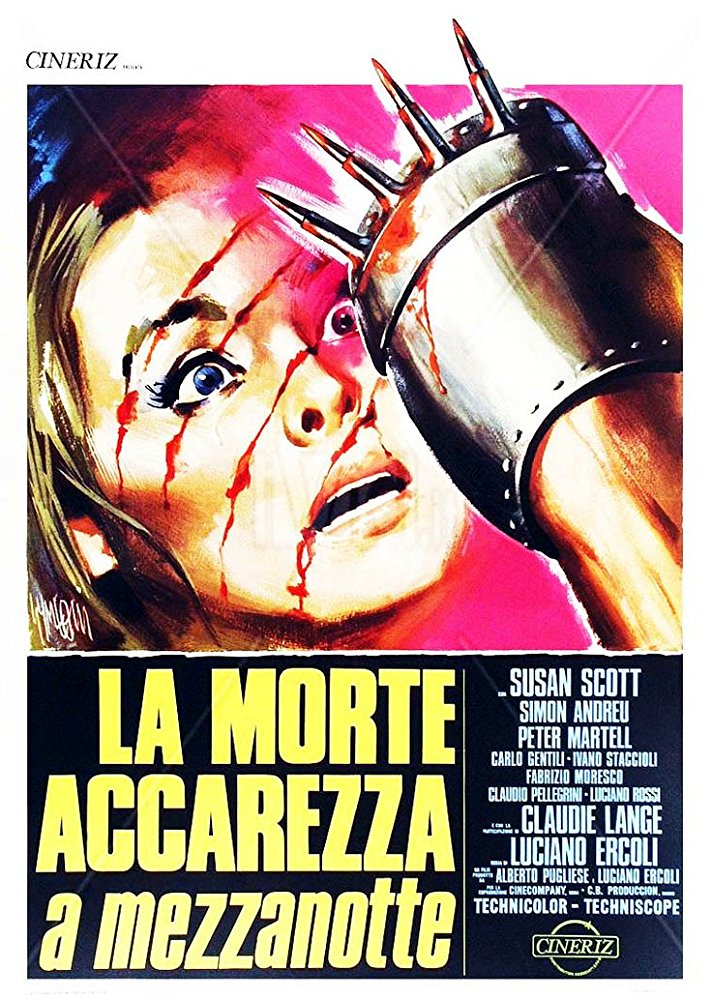

The weapon used here is also novel, being an iron fist with spikes (which, in another logic-gap eerily reminiscent of Cold-blooded Beast seems to be on open display in the insane asylum). You may wonder why every character seems to use the same weapon, or at least a version of the same weapon, but don't forget we're operating in a closed-off world here, where iron fists are the only weapons available. Until the latter stages of the film anyway, when knives and guns make a belated appearance. But still, marks to the makers for originality.

The ending's main twist isn't too bad, possibly because there's so much going on that we've almost forgotten that we should be looking at our roster of characters for suspects. Well, you might have forgotten about that; I definitely didn't. I definitely didn't at all, at all. It all leads to a fun chase/fight sequence on a roof which plays like a slow-motion take on the ending of Ichi the Killer. You'll also get to see Simon Andreu's pleasingly idiosyncratic headbutting technique not once, but twice. And as a bonus there's the worst parking job in history, when Valentina and her beau arrive on motorcycle at an art exhibition. What more could you want?

|

|

Oh, and there's that mother thing. It's far from a running theme, but there are a couple of odd scenes in which Nieves Navarro, as Valentina, plays mother to a couple of Japanese children, who are (nominally) under the care of her part-time lover. These interludes do show a softer side to the character, but it's hard to escape the feeling that Ercoli was recasting her as a domesticated woman, after her previous fiery sexpotism. Of course, as anyone who's familiar with Joe D'Amato's work, and can Google 'Does Nieves Navarro have children' will tell you, the Japanese kids seem to have had the opposite to the desired effect. They should be ashamed of themselves.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed