Jean Reynaud (not Jean Renault off Twin Peaks, although Michael Parks did work with Lenzi later on) is the most French of Frenchmen: brooding, pouty, speaks English weeth an assent, and loves a bit of philandering. He justifies this latter quality-slash-failing to one of his conquests by explaining that he's been married for three whole years, so naturally it's perfectly understandable that he openly covets everything with a vagina which passes within a hundred feet of him. Anyway, Nicole, an American woman, moves into the apartment above the one he shares with his poor wife, and she (Nicole) seems to be stuck in an abusive relationship with a very German man called Klaus. Jean falls in love with Nicole (veeeeery quickly) and she reveals that her appearance in his life wasn't as serendipitous as it initially appears, as Klaus has been paid to murder him and she's the bait. Who has paid for Jean's murder (I'll give you one guess)? Why does Nicole tell Jean this? And why doesn't Jean do anything to prevent Klaus from killing him?

Yes, that's right - Klaus does indeed follow through and kill Jean. Except, wait - why is Jean leaving threatening notes for his wife, despite being dead? It's not like he's still alive or anything, right? I mean, sure, the actual murder happens off-screen (/out of sight of everyone but Klaus) and Jean's body was too badly burned to be properly identified (a staged motor car death - possibly the defining trope of Lenzi's early gialli), but he's still dead, right?

This is basically the central mystery of the film: is Jean really dead? As such, it essentially takes what would become a standard surprise twist and places it front and centre. As such, there's no room for a last minute left-field 'despite what you'd assumed he's actually still alive' revelation, as we've spent the whole time since Jean's 'murder' inhabiting that left field, combing the soil for clues. And so, even though this film was made in 1969, before the giallo really took hold, already we have an example of the filone deconstructing the mechanics of a soon-to-be common plot twist (and playing with twists to the twist).

It's probably the giallo which is most indebted to Les Diaboliques - an influence which screenwriter Ernesto Gastaldi has readily admitted. Jean isn't as overtly mean as Michel in the Clouzot film, but he is a complete pussy hound, so you can understand why his wife Danielle is a bit fed up. An early scene in which the aforementioned couple drive around Paris discussing marital ennui is very on-the-nose, dispensing with thoughts of subtlety or subtext in favour of having the characters lay bare the failings of their marriage over the course of a two minute chat. Though Jean's subsequent behaviour - he drops Danielle at a shop and sits outside in the car to wait for her to return, only to catch a glimpse of Nicole and immediately drive off without a second thought for his wife - does probably the previous dialogue exchange redundant, as it conveys the same info as succinctly as the conversation had.

The film largely takes place in Paris, as noted, but does, of course, include a retreat to the coast for a romantic sojourn. It has to be sad that location doesn't quite play as important a role as it does in other Lenzi films - they may have only had a couple of days in Paris to shoot exteriors, but whatever the reason, the sense of place gradually fades away over the course of the film. One could say that this mirrors Danielle's failing and fading sense of self, and her increasing feeling of detachment, but that would be bullshit.

The film doesn't actually contain a ton of plot or incident, but it nonetheless flew by for me. Context is always important when viewing a film - one's mood, the circumstances in which the film is screened etc can hugely affect one's perception of the product - but I really was amazed at how quickly it whizzed by, which is a pretty big indicator that I was hugely enjoying it (also I know for a fact that I was enjoying it, which is a bigger indicator). The script/plot is a tad lightweight, but at the same time you get the feeling that the film is aware of this. At least, based on what Lenzi's said in interviews, he was aware that the script was a tad lightweight, and so he tried to make up for it in other ways. There's nudity (Beryl Cunningham doing her exotic nude dance thing), and there's wacky dialogue ("The atmosphere here is more libertine every day. I hope you don’t find that very awkward." "Well, it’s rather surprising.").

There's Horst Frank skulking around being threatening (and you'd really have to ask how these giallo characters were so efficient at spying in the pre-smartphone era - they always manage to be in the right place at the right time without having been informed as to where that place or time was). There's a great Riz Ortolani score (and a not-so-great theme tune). There's Jean-Louis Trintignant, one of the coolest actors of all time, flirting with the concept of 'acting' versus 'non-acting', and just about getting away with it cos he's so goddamned cool.

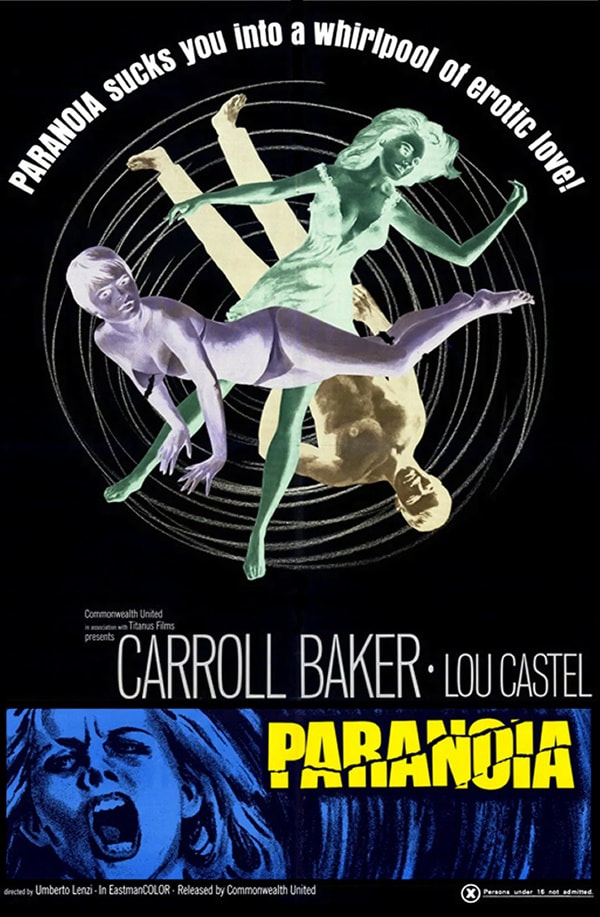

There's a kissing scene which lasts nearly a minute and which involves a classic old-school movie kiss - no Frenching (ironically) to be seen, just two people being still-as-statues with their lips locked (to be fair, JLT's detached style wouldn't really suit a vigorous tonguing). There's Carroll Baker, less put-upon that putting-upon for a change and revelling in it. There's Erika Blanc, still popping out her baps at the drop of a hat. There's the crazily-contrived scene where a woman manages to describe the ferociously blond Horst Frank without once using the word 'blond', thus making him sound like JLT, with neither Danielle nor Nicole, who are ostensibly questioning the woman to try and ascertain whether Klaus or Jean is renting a room in a hotel, bothering to broach the hair colour topic. There's some 'groovy' dancing, as was contractually obligated in 60s gialli. And there's a damn enjoyable film, which represents no-one involved's best work but which goes down even easier than a philandering Frenchman.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed