Lucio Fulci, playing himself (or a very similar character who has the same job, face and body as him, but with a different voice-he was dubbed by someone else in every version-and a made up title [Doctor]) is gradually unravelling. He's knee-deep in production on his latest gore epic, and having increasing trouble distinguishing reality from fantasy. As he seeks solace in the metaphorical arms and literal mind of a psychoanalyst, local prostitutes begin to turn up dead. Does the trail of destruction lead, as he himself believes, to Fulci's own door?

No, it doesn't-the psychoanalyst is the killer. That's not overly a spoiler, as he lays bare his fiendish plan to frame Lucio for his killings at the half hour mark of the film, which I would deem to be early enough to not constitute a spoiler. If you disagree, I can only apologise. However, to approach this film as a mystery film is to miss the point (and I can speak from experience; see opening para). It's really more an exercise in self-satire/parody, with Fulci simultaneously embracing and disparaging his reputation as a gorehound director. Saying that, much of the film-certainly the bulk of the middle third-consists of gore clips recycled from other films he'd produced or directed, so the self-examination conceit is likely the result of expediency as much as a genuine wish to interrogate his career and reputation.

He's certainly not afraid to dive wholeheartedly into the role and 'character', one early sequence constructed around orgy clips from his own Ghosts of Sodom making him come across as a demented old pervert. The set-up was possibly conceived as an excuse to take another pop at one of Fulci's favourite targets (along with the church): psychoanalysis (apart from being an excuse to recycle a lot of old footage). The psychoanalyst (/psycho analyst) is shown to be exploiting his patient for personal gain, and he salaciously gets off on watching Fulci's goriest work. Fulci himself makes reference to the cliché of horror films inspiring real-life violence, and that's exactly what does happen with the good doctor here.*

However, the fact that the on-screen violence is shown to be inspiring the 'real' life murders of the doc suggests an ambivalence on Fucli's part towards his work and cinematic violence in general. Far from repudiating the (ridiculous) theory linking on- and off-screen violence, he himself is influenced by the power of his filmic work to such an extent that he seems unable to distinguish between the two. So, we can interpret the inclusion of the psychoanalyst as a dig at what he sees as an exploitation of patients, and possibly an over-reliance on the power of images within that profession, but there's also an unquestionable ambivalence towards the power of the images which he himself created.

Another way of looking at it would be to simply say that his own career, and thus self, was consumed by the power of the violent image to such an extent that it left precious little else. Certainly on a professional level, by the time he made this film he was only able to secure budgets to make horror films, and barrel-scraping budgets at that.

So, let's deal with the film itself a little bit. It does bear some structural similarities with gialli, with a killer targeting prostitutes around Roma, and a bewildered central figure struggling to prove their innocence. However, the film takes almost every possible opportunity to subvert standard giallo practice, and could thus almost be seen as an anti-giallo. To give but a few examples: the killer outs themselves before any murders have been committed, the central character has no part in proving his innocence, and the final confrontation between killer and police occurs entirely off-screen. The police, in fact, play absolutely no part, with the Chief Inspector being on holiday for the duration of the film (and presumably not viewing the newly-active serial killer as worth abandoning the holiday for).

The murder scenes, which are mainly culled from existing films, show the difference between a stalk-and-slash set piece and a gore scene. These aren't necessarily mutually exclusive, as a tense stalk-and-slash can easily be followed by a gore-heavy murder, but gialli tended to contain examples of the former. We get a couple of tense scenes here, courtesy of giallo/slasher hybrid Massacre, but the rest of the inserts are exercises in special effects, which, shorn of any context, quickly lose any inherent power to shock. As a general rule, the camera stays still for gore scenes, its placement designed to showcase the special effects, whereas for tense stalk-and-slash sequences, the camera glides around the characters, functioning as an invisible net closing in on its victims. Even the stalk-and-slash scenes from Massacre don't really work when viewed here, as there's no real tension generated by placing characters we've never met before in peril. A talented director could, of course, potentially make an amazing standalone stalk scene, but that label doesn't really apply to Andrea Bianchi, who made Massacre. However, what little he does accomplish with his forest canoodling scenes merely highlights the lack of punch and affect afflicting the rest of the insert scenes.

The fact that the audience knows the identity of the killer leaves Fulci as the only real presence in the film who's operating in the dark. He functions as a kind of audience cipher for much of the film-particularly the insert-heavy middle third-standing around and watching the horrific goings-on, but powerless to intervene. (This is, of course, has much to do with the impossibility of editing him into already-existing footage.) He's impotent in the face of the horrific goings on, and clueless as to the identity of the murderer, almost as if Fulci is trying to create a cut-price copy of Dario Argento's audience-culpability treatise contained in his then-recent giallo Opera.

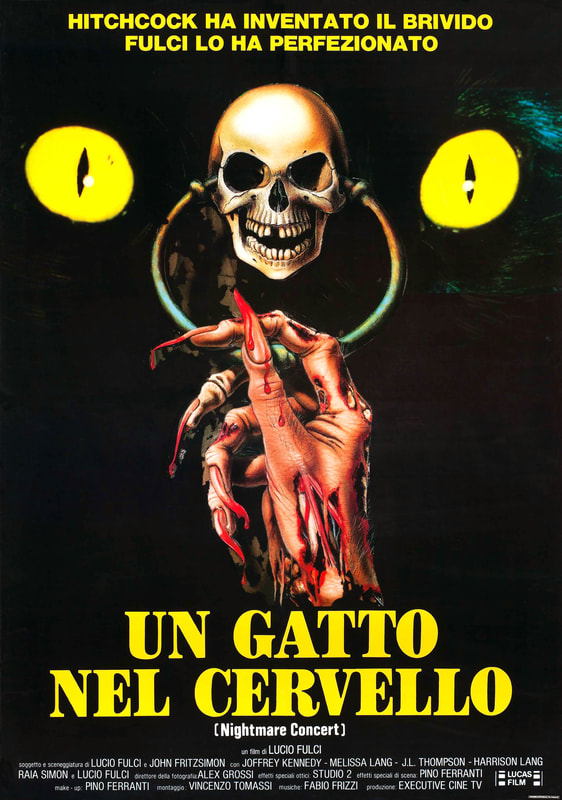

The film's not unwatchable-Fulci actually commits gamely to proceedings, and the interweaving of the old footage is occasionally neatly done, not least when he recruits Robert Egon to reprise his role from Ghosts of Sodom (although the remainder of the Sodom footage is terribly shoehorned in, so he giveth and taketh at the same time). If there's any serious attempt to get to grips with his legacy, we can only conclude that he's reached a kind of uneasy truce with his work, as the final scene breaks the fourth wall with the wrapping of the filming of A Cat in the Brain, and he contentedly sails off into the sunset (on a yacht called 'Perversion') accompanied by a busty brunette. The truth is likely that he was less-than-satisfied, both with his career at this point and this film in particular, but given the paucity of budget he's done OK. Even if he clearly doesn't know how to turn on a microwave.

*The doc articulates the issue quite succinctly in an early session with Fulci, telling him that he's struggling due to a "breaking down [of] the boundary between what you film and what's real." This is accompanied by a portentious zoom into his face, denoting this as an Important Moment in the film. The session begins (onscreen, at least) in slightly more prosaic fashion, the doc mentioning that the recent manifestations of Fulci's mania have involved a (very specific) fear of "hamburgers and gardeners." This leads to Fulci describing his interactions with both (which we've already seen), despite the fact that he must have already just told the doc about them, hence the doc's comment which opened the scene. This is a classic example of filmic dialogue which bears no relation to how people actually talk in real life (something not uncommon in Italian genre films).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed